A Review of The Case for Colonialism

The Case for Colonialism is a 2017 article by political scientist Bruce Gilley. It argues that colonialism was net good for colonized populations and even that it should be re-introduced today. The editors note gives a good sense of the reaction that this piece received after publication.

Editor’s Note: NAS member Bruce Gilley’s article, “The Case for Colonialism,” went through double-blind peer review and was published in Third World Quarterly in 2017. It provoked enormous controversy and generated two separate petitions signed by thousands of academics demanding that it be retracted, that TWQ apologize, and that the editor or editors responsible for its publication be dismissed. Fifteen members of the journal’s thirty-four-member editorial board also resigned in protest. Publisher Taylor and Francis issued a detailed explanation of the peer review process that the article had undergone, countering accusations of “poorly executed pseudo-‘scholarship,’” in the words of one of the petitions. But serious threats of violence against the editor led the journal to withdraw the article, both in print and online. Gilley was also personally and professionally attacked and received death threats. On the good side, many rallied to his defense, including Noam Chomsky, and many supported the general argument of the article. We publish it below in its entirety, conformed to U.S. English and our style.

“The Case for Colonialism” by Bruce Gilley

The piece itself is only 19 pages long and it doesn’t contain any graphs or tables or much data at all. It’s a short collection of quotes, anecdotes, and arguments suggesting positive effects of colonialism.

For example, Gilley notes that evaluating colonialism requires evaluating the counterfactual of what colonized countries would have looked like without colonization. This is an important point that critics of colonialism rarely engage in. But Gilley only lists a few example countries like China, Libya, and Ethiopia without evaluating their performance compared to countries with more colonial history. The only other evidence is an anecdote about the British crackdown on Bantu rebels in the Mau Mau rebellion possibly preventing genocide. Gilley gestures towards this more empirical study of colonialism’s effects which itself only a literature review without any graphs and takes a non-committal stance on colonialism’s overall effect.

Next, to show that colonial rule wasn’t seen as illegitimate, Gilley includes a couple of man-on-the-street quotes from people wishing for the return of colonial government, supportive quotes from a few other social scientists, and a vague point about how native’s migration to colonial cities and support during the World Wars shows that many natives saw colonial regimes as legitimate. He doesn’t seem obviously wrong here, but again the lack of data is disqualifying.

Finally, Gilley points out the costs of anti-colonial revolutions and the poor performance of post-colonial governance. This is surely important to consider in a debate over colonialism, but again Gilley simply doesn’t have the data or research design necessary to evaluate how bad these outcomes are compared to the counterfactual of continued colonization.

Gilley’s article succeeds in pointing out the vague outlines of interesting and important questions about the costs and benefits of colonialism that have been dismissed by many academics for quasi-religious ideological reasons. The vitriolic excommunication campaign waged against Gilley in the wake of the article is strong evidence that anti-colonial ideology has been shutting down research on this question.

There are good ideas that have been wrongly maligned or dismissed because of a word-association with colonialism e.g Paul Romer’s charter cities and the ongoing battle in Honduras over Prospera.

But Gilley’s exclusion of the 15th through 18th centuries and the Congo free state from his definition of colonialism is arbitrary and clearly self-serving. And again, there are no tables or graphs in the piece. You just can’t make a case for colonialism without this stuff.

The Case for Colonialism

That’s the actual article “The Case For Colonialism” by Bruce Gilley; too sloppy, short, and vague to make the case he wants but still an interesting piece and a useful balance to the extreme anti-western dogma of academia.

But moving beyond the article, is there a legitimate case for colonialism?

I would begin by making the now banal observation that institutions are the most important determinant of wealth differences across countries today. This is perhaps best shown by natural experiments where institutions are varied in an environment where most other important variables are controlled. North vs South Korea, Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Singapore or Taiwan vs China, the Dominican Republic vs Haiti, or East vs West Germany.

There is also the Deep Roots/Garrett Jones style literature showing that the ancestral geographic distribution of a nation’s population might be important for modern incomes in addition to institutions, or might be the upstream cause of better institutions. Think about New Zealand vs Papua New Guinea. Both are incredibly isolated, mountainous, jungle-y islands but one imported British people and their institutions and is among the richest countries in the world and the other did not and is among the poorest.

These literatures establish at least that colonialism is going to be incredibly important for global wealth differences. Institutions and people are the most important factors and colonialism is shipping them all around the world.

But did this end up being good on net? There is lots of economic research on this question.

The most famous is Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson. They want to test the effect of institutional quality on GDP per capita, but regressing institutional quality on GDP per capita won’t do. There is obvious reverse causality and confounding factors like geography that cause both. So instead they look to colonization as source of variation in institutional quality.

However, Europeans self-selected into regions with favorable climates and natural resources and those might cause higher GDPs on their own regardless of the institutions that settlers brought. Instead, they use historical settler mortality as an instrument: high mortality made settlement infeasible and led colonizers to establish extractive institutions while low mortality allowed Europeans to import more of their people and institutions. Sorting countries by European settler mortality creates groups which differ a lot in terms of their institutional quality, but arguably do not systematically differ in terms of other underlying advantage that might cause GDP growth.

They find that the countries who are predicted to have a low institutional quality score based only on their historical settler mortality also end up having much lower per capita incomes today. A one point increase in predicted institutional quality (on a ten point scale where Nigeria is 5.6 and Chile is 7.8) is associated with a bit more than a doubling of per capita GDP today.

This is definitely suggestive evidence that the type of institution brought by colonization matters a lot for modern incomes, but their instrumental variable almost certainly violates the exclusion criterion: settler mortality affects wealth through non-institutional channels. Higher European mortality happens in places that are hotter, have more jungle, fewer domesticated animals and plants, etc. These places all had much lower incomes long before colonization too! They try to control for this with other geographic variables and still find that lower European settler mentality has big effects on modern incomes, but one can reasonably disbelieve these results.

There is a better identification strategy in a less famous paper by James Feyrer and Bruce Sacerdote that looks at colonization of islands. They use another instrumental variable where they sort islands based on the prevailing wind speed and direction around the islands. Islands near favorable winds were easy to reach for explorers in the age of the sail and thus were colonized longer and more intensively, but wind patterns don’t affect many other determinants of modern GDP since they are now much less important for trade and connection.

They find that the islands that spent more time as a colony as predicted only by wind speed and direction are significantly wealthier than those islands with short predicted colonial histories. There are also important differences based on which country colonized the island, with the biggest benefits coming from countries with better institutions and deep roots.

Melissa Dell shows that even the extractive Dutch sugar cultivation in Java persistently increased incomes, education, and health outcomes for villages near the Dutch sugar plantations.

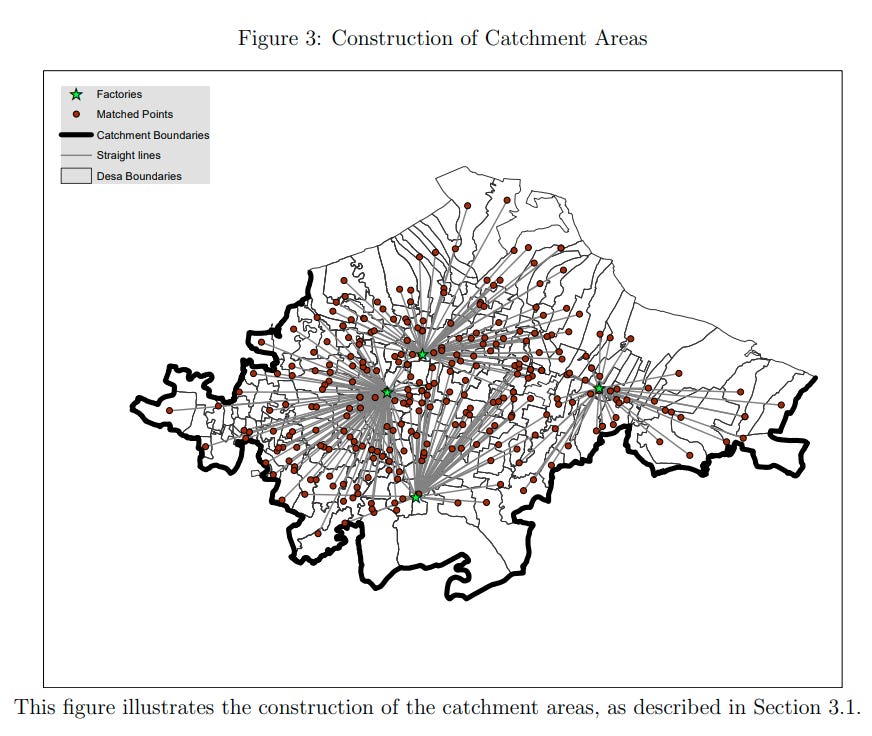

We show that areas close to where the Dutch established sugar factories in the mid-19th century are today more industrialized, have better infrastructure, are more educated, and are richer than nearby counterfactual locations that would have been similarly suitable for colonial sugar factories. We also show, using a spatial regression discontinuity design on the catchment areas around each factory, that villages forced to grow sugar cane have more village owned land and also have more schools and substantially higher education levels, both historically and today. The results suggest that the economic structures implemented by colonizers to facilitate production can continue to promote economic activity in the long run.

Banerjee and Iyer (2005) examine how land revenue systems established by British colonizers affected long-term development within India. They find that areas where revenue collection was assigned to existing feudal landlords show significantly worse outcomes post-independence than areas where the British directly administered tax collection. Areas with less direct British control had 23% lower agricultural yields and 40% higher infant mortality decades after initial British control over India. They avoid the influence of confounding variables somewhat by comparing otherwise similar neighboring districts with varying degrees of British tax collecting.

There is also David Donaldson’s classic paper on the British Raj’s railroad investments which had massive positive effects on incomes and plausibly would not have been built by the fractured indigenous polities that preceded the Raj since they would have struggled to internalize the cross-border externalities of transportation investments.

There are many more papers on similar topics than I can summarize here, but all of this research is consistent with a story that colonization can have some big benefits if the colonists actually try to import the right institutions and people.

Comparing these long-term, compounding economic benefits to the horrible atrocities committed in service of colonialism is difficult. Moreso because those must be weighted against the other tragedies that would have taken place in the feudal or tribal societies that colonization destroyed. My point estimate on colonialism’s net effect is negative with a confidence interval that includes zero.

Whatever the net effects, the evidence does suggest that indiscriminately dismissing ideas and practices if they have any association with colonialism is prejudiced. We know that institutions and people are the most important determinants of national wealth. So we should try hard to spread the right institutions and people around the world so that the whole world can be as wealthy as the west.

If that “smacks of colonialism” or sounds similar to the “civilizing mission” of the Victorian age, that doesn’t automatically make it bad. There are obviously huge mistakes from the colonial era that we need to avoid. But there are also important successes worth studying.

I won’t make Gilley’s mistake of taking a strong position on this complicated issue with only a few pages of argument and citations. I don’t think Gilley argued particularly well for his favored conclusions, but questions about the benefits of colonialism deserve rigorous study rather than ideological dismissal.

I wasn’t impressed with the Case for Colonialism article. The backlash was overblown—not because the argument was strong, but because it lacked substantial data. I remember the article rested on emotional appeals to the issues with Cabral, the Guinea-Bissau leader. It’s better to let ideas be published and then critique them with evidence.

I’m open to charter cities, but they’re a mixed bag. Some, like Fordlandia, were failures, while Shenzhen is arguably the most successful SEZ ever. Hong Kong and Macau serve as strong examples of colonial economic success. To say that charter cities will work because of the existence of Hong Kong & Macau isn't really a slam dunk argument when you know the success and failures of these programs in different areas.

I wrote about the pros & cons of SEZs/charter cities here if you are interested: https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/special-economic-zones-a-premier

A very crude way to test the “case for colonialism” is by comparing colonized vs. non-colonized African countries, mainly Ethiopia and Liberia. Ethiopia defeated Italy in 1896 and remained sovereign in the League of Nations until Italy occupied it in 1936. Ethiopian rebels fought until liberation in 1941, and historians and Ethiopians will say Ethiopia was briefly occupied, but never colonized. Liberia was independent since the 1870s. Based on the Maddison Historical GDP data, most African colonies were wealthier than Ethiopia in 1960, though Liberia was richer than many African nations at the time—albeit under Americo-Liberian apartheid.... so incomes were horrifically skewed. Granted the counterfactual is just two countries... but it shows how inconclusive to say colonialism was since you had Ethiopia worse off than the colonies and Liberia "better off than the colonies (for a small few Americo-Liberians)".

Fast forward to the 2020s, and the story shifts. Over half of Africa has moved to at least lower-middle-income status, while Ethiopia and Liberia remain among the poorest, with Ethiopia only about to approach lower-middle income this decade & Liberia has been ruined to low income status through its civil wars. You have some moderate "success stories" with some upper-middle income African countries like Botswana, Namibia, Mauritius, and Seychelles (again with all the caveats... Botswana and Namibia are extremely unequal... Mauritius and Seychelles basically live off tourism, flag of convenience, & offshore finance and have small populations). But the point is now you have 10 Sub-Saharan African countries poorer than Liberia and 20 poorer than Ethiopia out of the 48 Sub-Saharan African countries. But I would argue the status of each African country has more to do with their history of post-independence governance more than if they were colonized or not.

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/world-bank-income-groups?time=latest

Overall, I remember that guy made strong declarative statements that had tenuous foundations.

Criticism of colonialism tend to be highly selective, focusing on European colonialism on non-Europeans to the exclusion of all else. The Ottoman Empire colonized much of Southern Europe. Russia and Germany conquered and settled Poland for many years. Britain colonized Ireland. The Barbary States raided for slaves across much of the Mediterranean coasts.

Obviously this caused lots of human suffering. But it's unclear that South Eastern Europe, the Mediterrenean coast, Poland and Ireland were greatly harmed by colonialism/slave raiding in that their national development would be much higher without it. (Communism and demographic change is another matter).

Likewise, the Belgians were not terribly pleasant. Neither were many African rulers. Queen of Ranavalona I of Madasgascar reduced its population by half during the early 19th century.