Boomer NIMBYs vs Zoomer NIMBYs

When someone opposes new construction in their neighborhood they give one of two explanations:

This will lower property values!

The first explanation claims that an increased supply of housing will lower the returns on their own investment in property, and that construction of higher density housing has negative amenity effects which threaten the character of their neighborhood.

The second is focused on gentrification and displacement of existing residents. New luxury housing and Whole Foods will bring in rich yuppies who raise rents and line the pockets of developers.

These two objections to new construction cannot both be correct at the same time, and they come from two non-overlapping groups of people:

Boomer NIMBYs vs Zoomer NIMBYs

Owner NIMBYs vs Renter NIMBYs

Negative externality NIMBYs vs Positive externality NIMBYs

Right NIMBYs vs Left NIMBYs

How can these opposite views share the same opposition to housing?

First, there are huge historical differences in each group’s experience of housing markets.

Boomers grew up in the 50s-60s when big gains in construction and transportation technology were shifting the supply of housing in cities outwards fast. This lowered prices. Median rents in New York state fell by 25% from 1940 to 1950 and rapid construction kept prices flat in New York City even as the population of the city surged. Government interventions in housing markets in this period were huge highway projects or urban renewal public housing that had negative amenity externalities. Boomers grew up correlating construction with lowered property values and negative amenities, so they predict the same when faced with housing construction in their own neighborhoods today.

Zoomers have only ever seen demand increases butt up against strict supply controls. Construction productivity has been worse than stagnant for several decades and onerous regulations make big infrastructure projects unattainable, like aqueducts were to the Visigoths. Housing supply is now much less elastic, which means that when demand for housing goes up, price increases a lot and quantity increases a little. At the same time, there is lots of demand for cities. Finance and tech are growing in productivity and population growth puts a constant pressure on the housing market. Every time zoomers have seen new construction its probably because demand has increased, so they also see prices go up.

The differing opinions of zoomer and boomer NIMBYs isn't just due to spurious correlation of different data. Housing demand can slope up in some areas and down in others, meaning an increase in supply could actually cause higher prices rather than just being correlated with them.

Imagine we rule over a massive metropolis and can set the maximum quantity of housing in our bustling city to whatever we want. Right now, our decree in non-binding and the equilibrium quantity of housing is determined by the usual technological and economic constraints.

We feel the city is too crowded and noisy so we lower the maximum quantity to below the current equilibrium. This has the expected effect. Less housing is available in the desirable capital city so more cash is chasing after fewer spots, bidding the price higher. Our supply restrictions might also make the city more desirable in some ways: there is more space for gardens and less traffic.

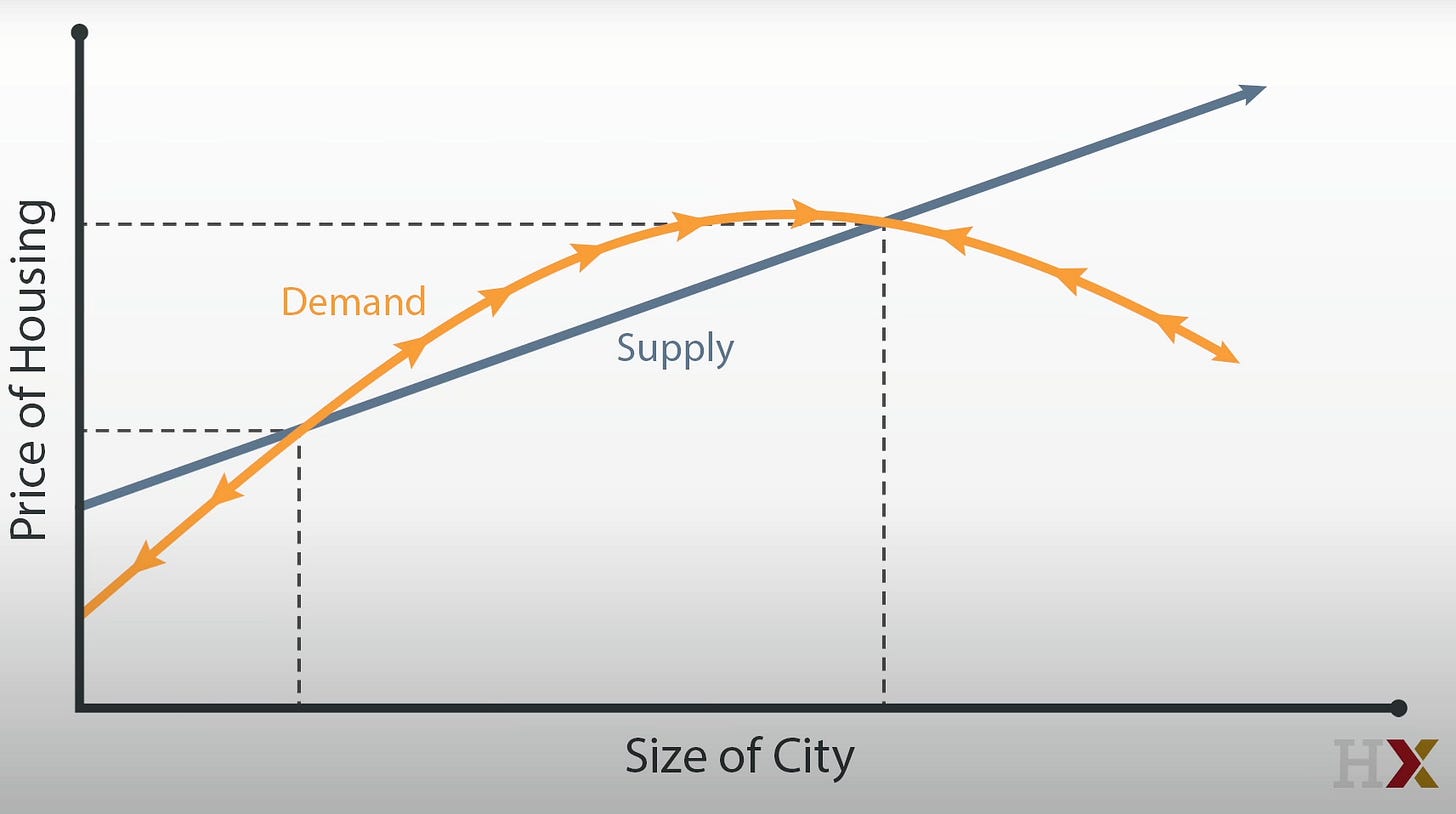

Feeling like this is working, we benevolently lower the maximum supply again, and again, and again. Prices tend to rise as the city becomes more exclusive but eventually we notice that below some maximum quota the price starts to fall as supply moves to the left. The people who might have bid for these exclusive spots eventually realize that they’ll be all alone in the city if they get them. Their friends, employers, and entertainment options have been pushed out to cheaper, denser locales. It is this desire to live near other people that can reverse the traditional direction of the demand curve.

So we get a parabolic shaped curve like this. If our supply cap is on the upward sloping part, then increasing the cap could raise housing costs even as more housing is available. Demand for housing must be shaped like this if we accept two claims: the cheapest housing is in empty North Dakota and, slightly decreasing the density of Manhattan e.g by raising minimum apartment size would raise prices.

Parabolic demand is another reason why zoomers might think that more supply raises prices; sometimes it does. Over the decades since the 1960s, housing supply has been shifted left and made more inelastic over and over again. As these supply constraints push the housing market equilibrium to the left, it gets closer to the upward sloping side of the parabolic demand curve. YIMBY supply reforms that increase construction will have a more muted effect on price, and possibly increase it as extra supply opens the city to more productive agglomeration benefits.

This is no reason to stop supporting YIMBY policies, though. Removing supply restrictions on the upward sloping part of the demand curve still improves total welfare, the benefits just come from higher populations in cities, faster economic growth, and new technological innovations rather than lower housing costs.

Empirically, most studies find the usual downward sloping demand even in the most restricted cities.

The construction regulations put in place by boomers in the 70s to protect their property values and “neighborhood character” have birthed a new generation of NIMBYs who oppose construction for entirely opposite reasons. Neither of them are correct.

Wow, you wrote a whole lot of words just to ignore the obvious. It's ENTIRELY possible for both to be true - it just depends on what the nature of the neighborhood is pre-new-project(s), and what the nature of the new project is. To cite just one example, in a good-sized neighborhood with both single-family and apartment building housing types, a project that replaces single family housing - especially one that puts apartment buildings on blocks that previously didn't have any - and even more especially on blocks that did not previously have any for several blocks around - WILL depress the future value of the single family homes. Period. Not even debatable. AND, if there is a sufficient amount of such development to fundamentally change the nature of the neighborhood into a more desirable place for apartment dwellers - "gentrification" - it will ALSO raise the rents for the existing apartments. Sorry, but this is just how real estate works in the real world that us real people have to inhabit.

If this is really hard for you to understand - i.e., you're not just posturing here, but really believe what you're writing - then, think of it this way: The two people in the quotes at the top of the article can BOTH be right because, more often than not, they are talking about different SEGMENTS of the housing market in that neighborhood. They may well break down into the categories you cite - after all, homeowners of well established single family homes in a nice-enough neighborhood (lets say an outer urban or inner-ring suburban 'hood originally built in the early 50's), and renters in older rental property in the same neighborhood, are likely to be members of different demographics on more axes than one. But that doesn't mean their arguments cannot be right - either individually or both at the the same time. Very, very often, at least one of them is right, and I am personally aware of quite a few cases where both are correct simultaneously.

Development, and even more so, redevelopment can be hyperlocal issues with real winners and real losers - and the losers frequently end up being losers through nothing they DID (unless you count NOT getting out of a changing neighborhood, "in time", that once suited them, but no longer does). These issues deserved open-eyed public discussion. Shouting "NIMBY!" and "YIMBY!" at each other, fingers pointed, is rarely helpful, and that's pretty much what your article promotes...