Does Cannabis Cause Schizophrenia?

Coming across a Psychology Today article on “The Link Between Cannabis and Psychosis” is a little like watching this clip from The Onion. It’s a well written article but someone in a different mental state might read it as “everyone knows you’re high and it’ll probably make you go insane.” I have taken enough econometrics to suspect that there might be some selection effects in the observational studies that this article mentions. I’ve also taken enough econometrics to wonder whether I could answer this question for myself. This post chronicles my attempt to do just that.

Background

Cannabis use in the United States has increased significantly in the last 20 years as an already enormous black market industry grew with new legal status. Even as cannabis consumption explodes, it remains illegal on the federal level. This means that getting federal funding and approval for studying the drug, especially with human patients, is difficult. Until 2021, only a single facility in the United States was allowed to grow cannabis for research purposes. Thus, little is known about the health effects of smoking cannabis compared to plausible substitutes such as alcohol or tobacco. A 2020 meta-analysis of the association of cannabis with schizophrenia found only 12 appropriate studies on the topic.

Despite the relative lack of research, there is still suggestive evidence of a connection between cannabis and certain types of mental illness, especially schizophrenia. A 2021 article which connected survey data of cannabis use and psychotic experiences to genomes in the UK biobank found that daily cannabis use was associated with a five percentage point increase in the likelihood of reporting hallucinations from 4% to 9%. Interestingly “A sensitivity analysis stratifying by sex indicated that the association of cannabis ever-use with psychotic experiences was significantly stronger among females than among males. Two particular types of psychotic experiences, auditory hallucinations and delusions of reference, also had significantly stronger associations among females.”

Still, this research design is vulnerable to selection effects. People who are more likely to be schizophrenic may be especially attracted to the effects of cannabis or they may use the drug to self medicate symptoms before they are diagnosed. To go beyond this associative evidence without the use of clinical trials, a quasi-experimental research design is needed.

Natural Experiment

Variation in the legal status of cannabis between US states might provide the perfect laboratory. If relaxations of legal status cause significant increases in cannabis consumption compared to states with similar trends who did not legalize, then we can look at the effects of legal status on schizophrenia without worrying about selection effects. We’ll know that legal status increases consumption, but we can be reasonably confident that people with higher rates of schizophrenia do not self-select into states with a higher chance of legalizing cannabis or cause their home state to legalize.

So does legalizing cannabis significantly increase its use? It might seem obvious that it does but there is some chance of selection effects here too so we should compare legal states to neighbors that never legalize but who had similar cannabis consumption trends before legalization.

Before Colorado legalized, cannabis use in Colorado and Idaho moved together, both affected by national level trends. But after Colorado legalizes the gap in use between them shoots up and the parallelism is broken. If Colorado had not legalized and continued on its parallel trend with Idaho the average cannabis use over the 2012-2019 period would have been around 5 percentage points lower.

Our choice of Idaho as the comparison above was somewhat arbitrary. It’s a nearby state and its trend looks parallel, but I just looked through the graphs of nearby states to find one that looked parallel and I didn’t check all of them. To make this process more precise, we can search through all of the states in the control group to find the weighted average of states that best match Colorado’s pre-legalization trend. Then we project Colorado and the weighted average that used to match it well forward in time. If nothing had changed, we would expect Colorado to continue matching its synthetic pair, but they legalized cannabis and consumption increased above the increases seen in their control group.

In this case the control group is any state that didn’t have recreational cannabis laws by 2019, so it includes states with medical laws. Synthetic Colorado is mostly Connecticut and Tennessee with a bit of Idaho, Utah, and Hawaii. To make sure that this jump isn’t just a coincidence, we can do placebo tests on the control group states that never legalized and see how Colorado’s deviation from its control group compares to these placebos that didn’t actually change their cannabis policies.

Colorado’s deviation from its synthetic control after 2012 stands out among the other states. So we can be confident that legalizing cannabis really does increase use, and its not just that legal states had lots of pot smokers already.

What effect did this have on schizophrenia?

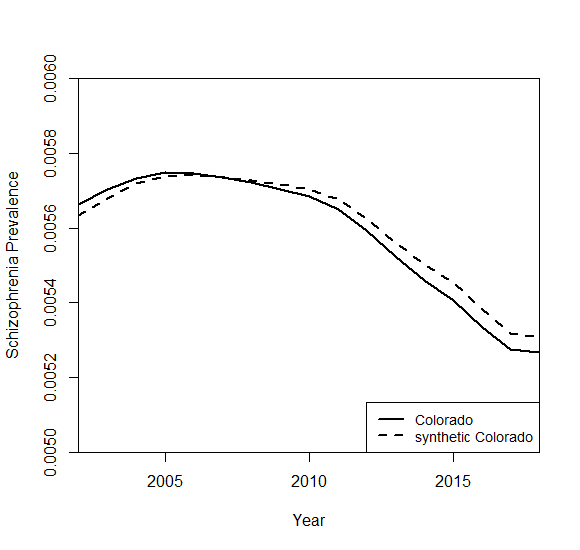

Essentially none and if anything a negative effect. How does this compare to control states?

It’s lower than most but certainly not separate from the pack as it was for cannabis use. Consistent with the 2021 nature article, females had an increase in schizophrenia rates relative to males, but inconsistent with that article they both had decreases.

So far we’ve only talked about Colorado, but all of these results replicate for Washington and Oregon, the other states that legalized early. You can check this everything else I’ve done so far using the replication and data files I’ve hosted on google drive here.

Caveats and Conclusion

This all seems like strong evidence that cannabis use does not actually cause schizophrenia. Before concluding this however, a few caveats have to be made. First is that there are only 7 years of data for Washington and Colorado and even fewer for states that legalized after them. It may be that Cannabis does increase risk of schizophrenia but only later in life or after many years of use. Second is to remember the old saying: “Garbage in, garbage out.” The data on cannabis use comes from a survey, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, so there may be response bias even though it is anonymous. Schizophrenia is a rare disease and it is difficult to track. I found the source I am using through Our World In Data who use data from the Institute for Health Metrics Evaluation at the University of Washington.

That Our World In Data uses this source is a good sign but there are some reasons to question the data. IHME’s database has data on hundreds of health metrics for dozens of countries over decades. With so many things to cover from so many different sources, I would be surprised if all of them were accurate. Relatedly, IHME is not producing these estimates with original research, they collect them from other research by putting a bunch of studies into a “meta-regression” model. This meta-regression process and the sources behind many of their estimates is opaque. Finally, the overall trends in schizophrenia just look weird.

The amount of parallelism between states makes me suspect that this is actually national level data that has been divided up between the states. Or perhaps more likely that there are only a couple of years of data points and the rest are just imputed using the same function. I searched for a better source of schizophrenia data at the state level but couldn’t find anything publicly available. If you know of anything, please let me know in the comments or email me at maxwell.tabarrok@gmail.com!

All of this is to say that even the best causal inference cannot fix data problems, and it seems like there might be some here. The IHME data isn’t random, it’s probably just low resolution. So the fact that we find a negative effect on schizophrenia rates tells us something, but it’s not conclusive. It feels a little off to end a blog post with an “I don’t know” but sometimes that’s the way the cookie crumbles. Hope you still enjoyed going down this research rabbit hole with me!

I think you have overlooked a lot of evidence that cannabis (particularly THC) causes psychosis - summarised in this thread https://twitter.com/psychunseen/status/1504138625713246210?s=46&t=h_aFsZlD-I_rxx3iml2TfA

- and also see this meta https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26884547/

Is the problem of finding this evidence that you’ve searched for associations with schizophrenia rather than psychosis more broadly defined? That’s all well and good but if you follow up people who experience cannabis induced psychosis, four years later roughly 1/4 to 1/2 transition to schizophrenia https://academic.oup.com/schizophreniabulletin/article/46/3/505/5588638#

1. Schizophrenia is diagnosed between the ages of 15-35, so the derivative of incidence might just capture the millennial cohort distinct from Gen X and Z. If net MJ consumption goes up but adolescent consumption goes down then macro scale analysis will be too heavily confounded.

2. The medical literature suggests an effect of regular heavy/daily use but not intermittent use; the risk is more like pain pill overdoses than tobacco carcinogens. If everyone smokes 1 extra joint per week because of legalization, that might affect marginal incidence in the 5+ joints-a-week population, but everyone else will be fine.

3. Cannabis can cause psychotic episodes, which shows it impacts the same systems that drive schizophrenia. But, it’s possible that someone who has multiple cannabis-induced psychotic episodes across years satisfies the DSM-V criteria but isn’t a ‘true’ schizophrenic. Does that make our priors go up or down?

I’ve done a bit of research on this topic earlier, which left me mildly concerned about weed and very concerned about the quality of illicit drug studies. Your post is a great attempt but GIGO. Thanks for the attempt tho.