Does Economics Flip-flop on the Minimum Wage?

Econ 101, 102, and the minimum wage

If economics is what economists do, then economics clearly does flip-flop on the minimum wage. If instead, economics holds some truth separate from the opinion of any individual professor, then the answer to the question in the title has to go beyond a trivial survey of economists’ opinions.

The supply-and-demand model that everyone learns in Econ 101 clearly repudiates the minimum wage. A binding minimum wage bans some transactions between people who are willing to work and employers who are willing to pay them, creating deadweight loss.

Monopsony

One relevant addition to this model is monopsony. A perfect monopsony is when there is only a single buyer of goods in a market. In the labor market, this means a single firm hires all workers.

The outcomes of monopsony are easiest to understand when considering a goods market. Imagine you're the sole buyer of apples and all the orchards from Washington to Virginia wait patiently for your quoted price.

You know that if you offer $1 per apple, the farmers can only afford to pick the lowest hanging fruit, and you'll get 10 apples for $10 bucks. If you offer $2, the farmers can afford break out the step-ladders and produce 5 more apples. Now, you get 15 apples for $30. If each apple is worth $3 to you, this is still net positive, since they only cost $2 each. But to get those 5 extra apples, you had to pay $20 extra dollars which is $4 per apple, and thus more than you're willing to pay.

If a minimum price was set and you had to pay at least $2 for all the apples anyways, you'd be better off buying all 15 than just 10. In a market with a single buyer, a price floor can raise price and quantity.

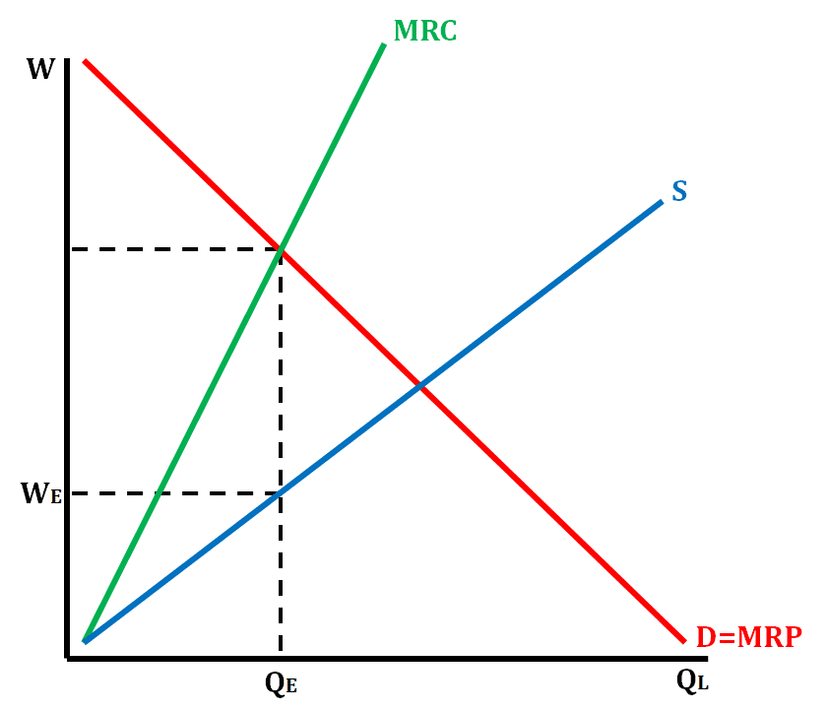

In the same way, a monopsonist in the labor market gets to choose how many workers are “produced” by setting the wage. Every extra dollar you offer brings more workers in, but just like for apples it also raises the price of all the workers who would have been produced at lower wages. Therefore, every additional hire gets more and more expensive, so the marginal cost of labor rises faster than the supply of labor.

The firm hires until this marginal cost equals the marginal revenue. But that sets wages and employment below the competitive level: the firm restrains hiring because their decisions set the wage in the industry and the additional cost of raising the wage to attract the next worker is too high, even though the average cost per worker would still be net positive.

From this monopsony baseline, the costs of the minimum wage are absent. If a price floor raises the wage above what the monopsonist wants to pay, you actually get closer to the optimal competitive outcome. Wages and employment go up!

But is Monopsony Relevant to the Minimum Wage?

Open eyes are enough to prove that the low-skilled labor market is not dominated by a single firm. On any commercial street there are bound to be several restaurants, retail stores, warehouses, cleaning companies, and gig-work apps available to hire low skill workers into dozens of positions, all competing with one another. More empirically, there are around 3 million establishments between firms in construction, retail trade, and food services. My labor market of universities and think tanks seems more likely to bear monopsony, and be in need of a minimum wage, having only around 5,000 firms. So if the low-skilled labor market is supposed to be monopsonistic, then the rest of the labor market must be much more so.

Economists these days, however, tend to generalize beyond the definition of monopsony as a market with a single buyer and instead identify it with upward sloping labor supply.

In a perfectly competitive world, it’s costless to switch between firms. If one firm lowers its wage below what’s offered by competitors, it suddenly finds itself with zero employees. One cent off and everyone leaves for a different job with higher pay. In other words, the elasticity of labor supply is infinite. On the graph, it’s horizontal.

It’s a difficult empirical problem to find wage changes that aren’t correlated with changes in firm or worker productivity, but research has pretty consistently shown that the elasticity of labor supply is not infinite, it’s more like 4 or 6.

The source of this finite labor supply elasticity is intuitive: it’s not costless to switch jobs. When an employer lowers your wage, you may consider quitting but before you do you’ll weigh the sting of lower pay against the risk of extended unemployment. The costly outside option facing workers means the number of firms they are able to costlessly switch between is exactly one. That creates the monopsony outcomes we analyzed above: Lower wages, less hiring, higher profits, and a counterintuitive response to the minimum wage.

It seems like this closes the case. It’s true that the low-skilled labor market has lots of firms, but search costs mean that firms can lower wages without losing all their workers. Monopsony therefore seemingly pervades every part of the labor market, and thus potentially justifies the minimum wage in many contexts.

Upward Sloping Labor Supply =/=> Monopsony Profits

The logic of search costs causing monopsony makes sense, but closing the case here would be a mistake.

The first puzzle facing the monopsony theory is the profit share of income. If the labor supply elasticity is as low as the studies predict and firms exploit this to enforce low wages, then firms should be making massive profits off of each worker, and thus the profit share of income should be ~35% when it’s actually only 10%.

The second puzzle is wages at large firms. In a standard monopsony model, a firm’s wage bill has to increase massively as it climbs up the labor supply curve to grow in size. This is the exact motivation behind monopsonists cutting employment below the competitive level. But in fact, larger firms pay only slightly higher wages than small ones do, suggesting that firms face an elastic labor supply which can flow in from other jobs in response to even small wage increases.

So despite the fact that search costs for workers do make labor supply curves less than infinitely elastic, firms seem unable to leverage this power into profits as the monopsony theory predicts while simultaneously being unconstrained by the upward sloping labor supply curve when growing.

Moen 1997, a foundational paper in the economics of labor market search, resolves these puzzles with the following observation: while firms have some power over current employees, they have to compete with each other for the attention of job seekers. If a firm posts a job offer with a low wage that would make them lots of profits, other firms are free to post more vacancies of their own and outcompete them for workers.

Additionally, search costs for workers are reflected as vacancy costs for firms. So a costlier outside option for workers (the prospect of taking weeks to find the next job), is also costlier for firms (going weeks with a vacant position). Search costs are a technological constraint on the matching technology of the labor market that prevent the full efficiency of perfect competition, but they don’t allow firms to get a free lunch off the backs of their workers.

Under these forces in equilibrium, all job offers make zero economic profits for firms. The posted wages are still below the marginal product of labor, but the wedge between productivity and wages is eaten up entirely by the cost of searching for jobs and filling vacancies.

But still, the labor supply elasticity is not infinite. Higher wages lower the recruiting time for vacant positions, but they don’t let them recruit the whole market at once. The other puzzles are also resolved. Firm profits remain at competitive levels, and firms don’t need to pay massive premiums to expand their labor force, they just post extra job offers at the same wages. If they post so many as to raise the aggregate tightness of the labor market (i.e the number of vacancies per worker), then wages do rise, but only modestly.

Models of labor search costs that lead to monopsony profits are missing either the symmetric impact of search costs on firms or the free entry of job offers or both.

The competitive search equilibrium is consistent with the empirical evidence (including the randomized control trials on the minimum wage) and it preserves the signs of the econ 101 comparative statics on the minimum wage. Unemployment goes up and deadweight loss is created.

Thus economics in itself, beyond the opinions of economists, is consistent on the minimum wage. Monopsony can overturn the standard minimum wage results, but only when there really are strong constraints on competition, usually coming from a market with a very small number of firms and restricted entry. The low-skilled labor market has too many firms and too few barriers to entry to support the monopsony power required to overturn the standard results on the minimum wage, regardless of what some economists will tell you.

Good article. Edit needed: “Imagine you're the sole buyer of apples and all the orchards from Washington to Virginia wait patently for your quoted price.”

The apple picking paragraph was nice - some of the details of monopsony tend to leave me over time, so hopefully it sticks now