Even Acts of God Can't Fix Permitting Anymore

Natural Disasters and Creative Destruction

Natural disasters have a long history of creating shakeups that can strip the rust off of decaying institutions, reset outmoded infrastructure investments, and simplify complex property rights landscapes. It is a sign of just how tightly constrained construction is today that natural disasters can no longer break through the bureaucratic binds of environmental proceduralism.

Three months after wildfires scorched Los Angeles, somewhere between zero and four rebuilding permits have been issued out of tens of thousands of buildings that were destroyed. The recovery from the 2023 wildfires in Lahaina, Hawaii has been even slower. A year and a half after the disaster, only 6 structures have been rebuilt out of over 2,000 that were destroyed, and permits have been issued for only a few hundred additional projects.

Creative Destruction Historically

Fires, earthquakes, bombings, and other disasters are obviously costly and tragic events. However, they can act as coordination mechanisms that help property owners make efficient investments in new infrastructure that wouldn’t have been possible to do on their own and as forcing functions on governments to allow urban land uses to fit market conditions rather than preserving existing interests. There are several examples of these effects from history that have been studied by economic research.

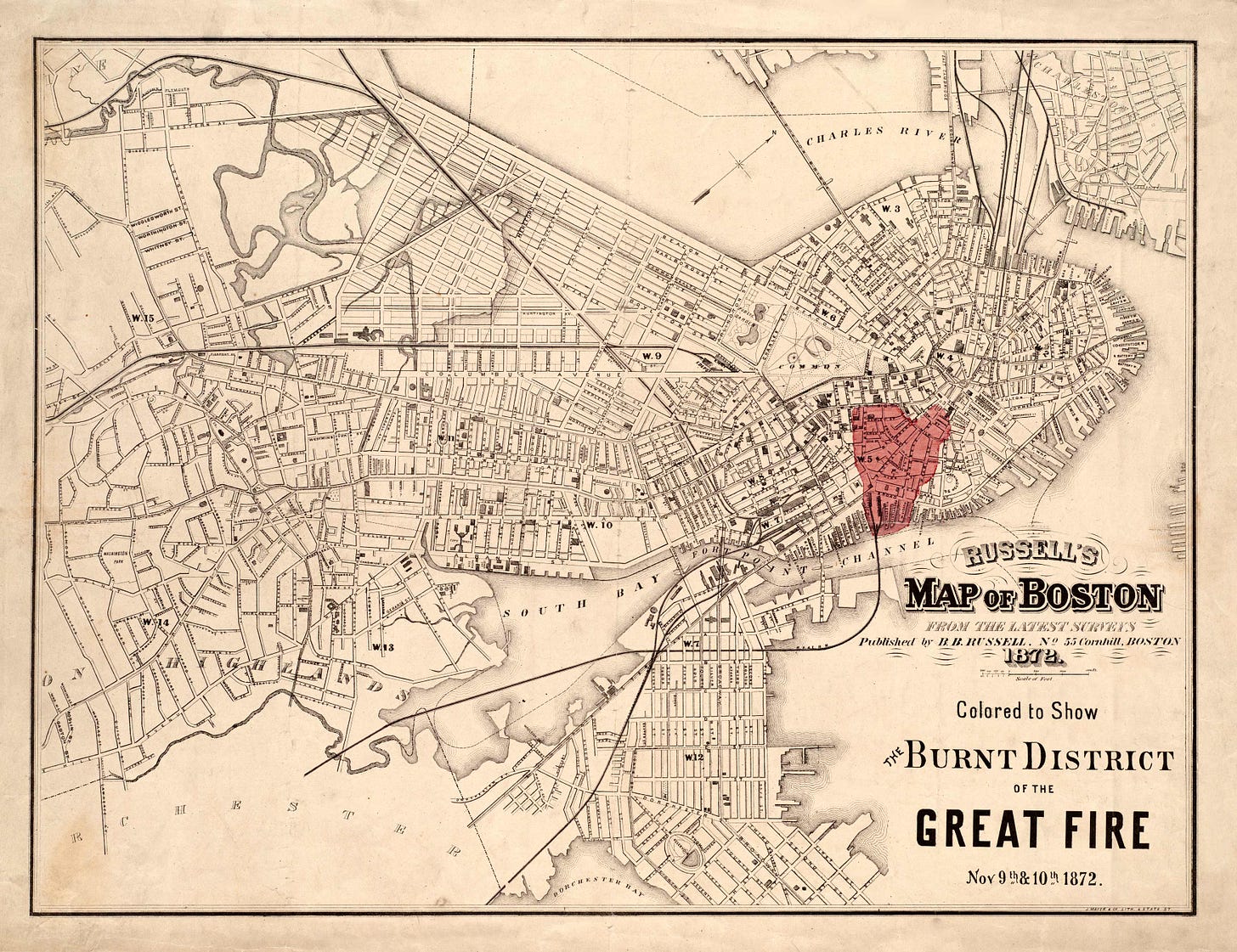

The oldest comes from the 1872 fire of Boston. It destroyed all of the buildings mapped in red below but after the fire, land values in and near the burnt areas rose by enough to more than offset the loss of building value from the fire.

According to Richard Hornbeck and Daniel Keniston, this extra land value came from the fire forcing all the landowners to rebuild their old buildings at the same time, thus internalizing more of the positive externalities of building quality. Here’s how that works: When a landowner improves the quality of their building, it raises their land value, but also raises the land value of surrounding plots. Higher land values incentivize more investment into building quality but usually, one improved building nearby isn’t enough to overcome the fixed costs of reconstruction for neighbors, so this positive land-value externality isn’t recovered, and property owners underinvest in building quality.

However, when everyone is forced to rebuild at the same time, there are no fixed costs to overcome; everyone is already planning a construction project. So if you invest in a higher quality building that will raise surrounding land values, your neighbors can immediately respond by raising their building quality which then spills back over into your plot in a virtuous cycle that results in everyone building intensively on their plots and raising surrounding land values far above their previous peak. The area of Boston that was burnt down in 1872 is, perhaps not coincidentally, now home to its tallest skyscrapers.

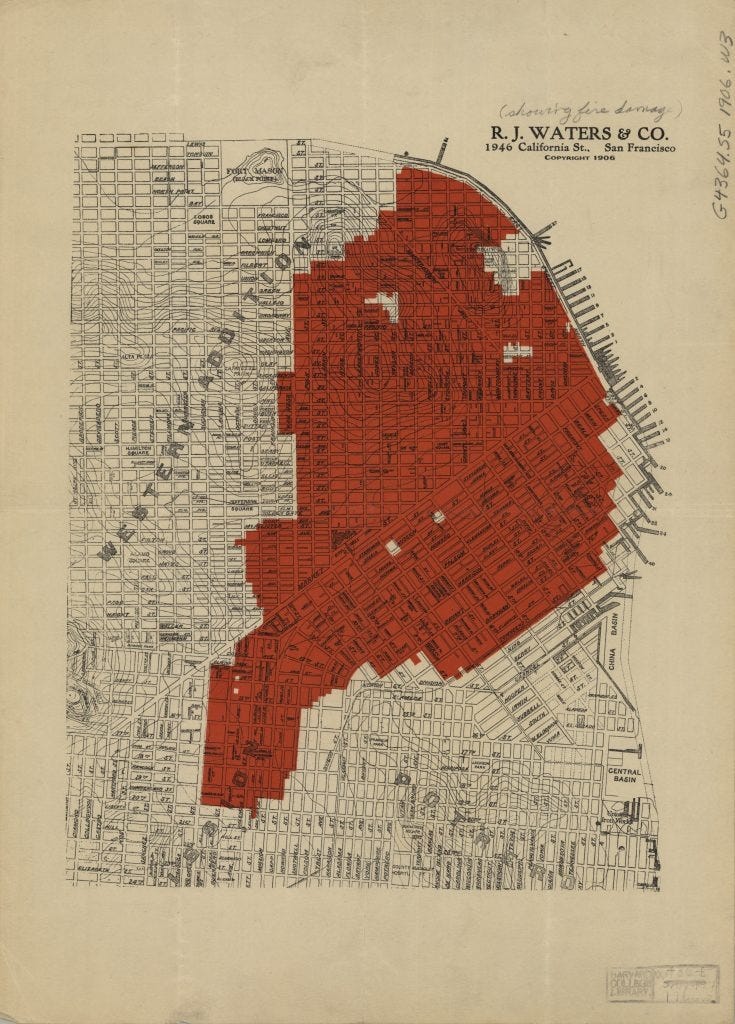

There’s a similar story in San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire.

Here, the author focuses on path dependence and fixed costs rather than on cross-plot externalities. Buildings are durable goods and they can stick around for much longer than the market conditions that incentivized their construction in the first place. This is why you can buy homes in Detroit for a dollar even though no one would ever build a home for that price. In the opposite direction, low density buildings can persist even after the optimal density rises far above what they can provide because the net present value of higher rents from a denser building can’t overcome the upfront costs of permitting, demolishing, and rebuilding.

The 1906 fire forced the decision. Landowners no longer had the lower rents from their older buildings competing with the upfront costs and future benefits of redevelopment, so they were incentivized to rebuild to the optimal higher density. After the fire, burnt plots got significantly denser; about 15 extra residential units per acre compared to nearby unburnt ones. Without resolving some externality or inefficient tax on redevelopment, this forcing function of the fire is still a welfare loss, but these frictions probably did exist as they did Boston and the rapid recovery after the fire created much of San Francisco’s modern urban landscape.

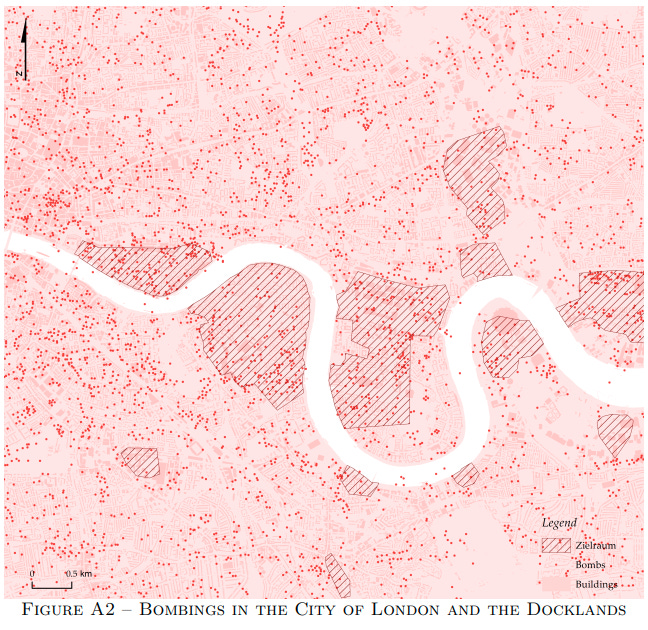

A final example with perhaps the largest positive effects took place after the London Blitz bombings during WWII. While not exactly a natural disaster, this example more explicitly involves planning regulations, rather than just development fixed costs or land value spillovers.

Gerard Dericks and Hans Koster exploit the variation caused by Blitz bombings to measure the costs imposed by redevelopment frictions which prevent higher densities and thus more productive agglomeration economies. London's strict planning regulations restricted building density and height but the Blitz destroyed many buildings that would otherwise have been historically protected sites and pushed local authorities to loosen rules for reconstruction projects. Areas with higher bombing intensity have since developed taller buildings and higher employment density.

The elasticity of productivity to building density as measured by this exogenous variation implies that doubling employment density leads to a roughly 20% increase in productivity. Counterfactual simulations suggest that if the Blitz didn’t happen, and heavily bombed areas of London had developed more like the areas that had been spared, increased redevelopment frictions would have reduced the total population of London by around 9%, with even larger decreases in the most productive central business district. Less density means less productivity so without the redevelopment allowed by the London Blitz, total economic output in the city would be roughly 10% lower than today's actual outcome.

Creative Destruction is Just Destruction Today

Returning to the present day, the creative destruction offered by natural disasters or other city resets seems unattainable. Our environmental permitting regime is so inflexible that rebuilding after disasters doesn’t feel like a release of development potential that was held back by previously fixed investments, it just feels like irreversible destruction.

Often, rebuilding after a disaster today can be even more restrictive than the original construction. Much of the building stock in the most restricted markets was built before hardline zoning codes and were grandfathered in with one-off zoning variances. When rebuilding, these variances no longer apply and new construction might be impossible. For example, 40 percent of the buildings in Manhattan could not be built today and thus couldn’t be rebuilt if they were destroyed.

There is a counterexample to this story that proves the rule of environmental permitting constraints and shows a path forward for revitalizing construction after disasters and in all contexts: the I-95 bridge collapse. After a truck fire beneath the bridge caused the structure to fail on an essential transport corridor in Pennsylvania, Governor Shapiro issued emergency rules exempting the reconstruction project from standard contracting regulations and environmental review. The temporary replacement bridge was ready to go in just two weeks.

Everyone knows our construction regulation regime is costly and slow, but when even the defibrillator-shock of a city-destroying fire can’t get the system to wake up, we have to declare it dead.

Wait you’re saying that modern America has become a bureaucratic nightmare of red tape? Congratulations, seems like your Econ textbooks book has finally caught up to the year 2015.