Intergenerational Mobility Part I

Intergenerational mobility (IGM) is at the center of debates about economic inequality and of our conception of the American Dream. If children’s economic futures are assigned by consequence of birth, then economic inequality is bound to persist and compound itself as our society is stratified into more and more disparate classes. If we’re free to move up and down the income ladder, however, then everyone has a shot at the top, and inequality represents true differences in marginal productivity. Debates over this topic are fraught with pessimism bias, virtue signaling, and cherry-picking, but in this post I attempt to cut through the ideology and get some useful insights into what intergenerational mobility is and what we can do to change it.

So, what is IGM?

There are two main measures of intergenerational mobility.

The first, called absolute mobility, compares the inflation adjusted incomes of children to their parents and sees if they are making more money. This is an important measure because it tells us whether children are becoming materially better off than their parents. It measures the real amount of resources and amenities that are available to each generation.

The second measure compares the income percentile rank of parents to their children. This is generally called the Intergenerational Elasticity of income (IGE), or relative mobility. It measures how much a parent's position in the income rank transfers to their kids. If there is an IGE of .6, then a one percentile increase in parent’s income rank will pass through a .6 percentile increase in income rank to their children on average. This is the more common measure, especially in international comparisons.

Why is intergenerational mobility important?

The importance of relative intergenerational economic mobility depends on some key assumptions.

First is that we want relative intergenerational mobility to reflect fairness and that a fair way to determine income is meritocracy where one’s income is directly proportional to one’s ability to produce valuable goods or services.

Second is that we need a model of what relative intergenerational mobility would look like under maximum fairness. This is a question I will dive into more in part II, but a baseline model of an ‘Equal Chance Economy’ where merit is randomly distributed with respect to parental income and each quintile has a 20|20|20|20|20 population distribution is a reasonable assumption to make a priori.

Now that we have these assumptions, we can interpret relative intergenerational mobility as a direct measure of the fairness of a society; how much it deviates from the idealized ‘Equal Chance Economy’ model. Deviations are important because they represent society passing over talented people because of an accident of birth. This is inherently unfair and it leads to a loss in economic efficiency as labor is misallocated.

The importance of absolute intergenerational economic mobility is more self evident. We want all nations and peoples to increase their control over resources over time. This is because resources are instrumental goods for everything else we value like health, length of life, happiness, peace, and culture.

Now that we know what IGM is, we can start to characterize its levels and growth in the US.

What are the levels of IGM today?

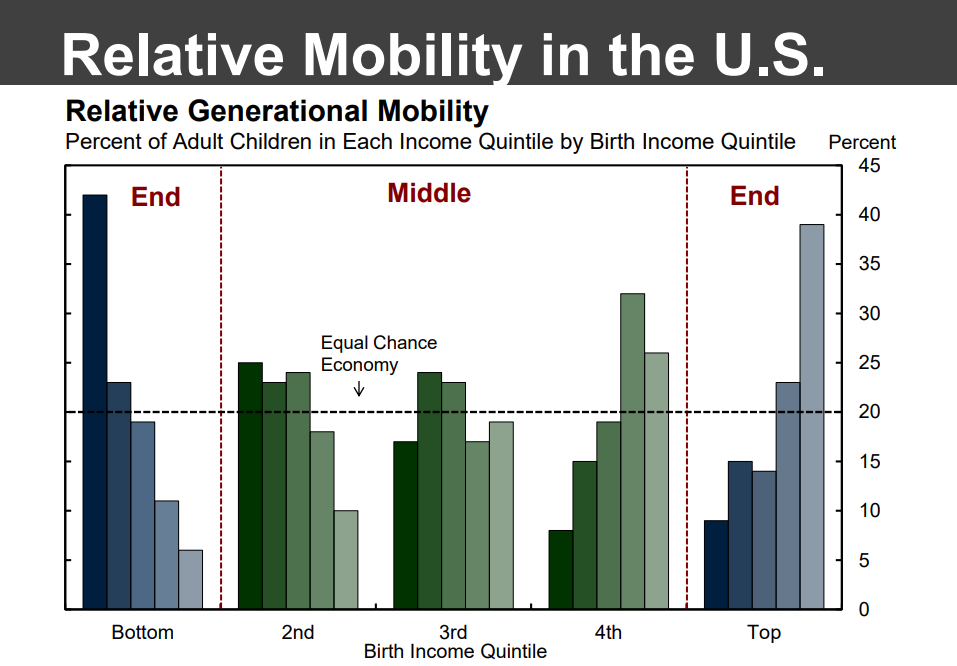

Relative intergenerational mobility today is significantly different from our theoretical baseline of an ‘Equal Chance Economy.’ Data from Julia Isaacson’s study of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and Census records link father and son incomes across multiple generations since the 1960s.

This graph breaks each income quintile into five bars which represent the percent of children born to parents in that income quintile get to other ones in the distribution.

The middle three quintiles are relatively close to the theoretically ideal ‘Equal Chance Economy’ and are very mobile. The two ends are much more sticky, with a prominent left skew. The bottom of the income distribution is much less mobile than any of the others, including the top.

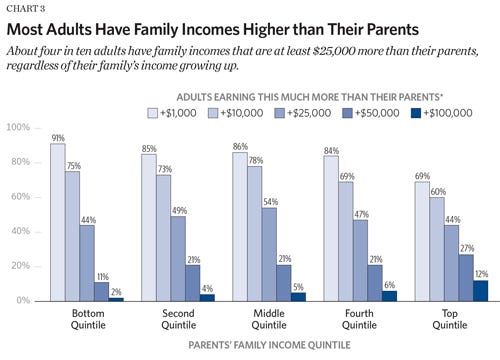

Absolute IGM paints a more optimistic picture

.Again, sourcing from the PSID, 67% of all children have a family income greater than that of their parents measured one generation apart at the same age. This is even better than it sounds for two reasons. Family structure has changed so there are more single family households, and the length of education and training has increased significantly so children are earlier in their careers than their parents were at the same age. Additionally, absolute mobility is highest for the bottom quintile.

Part of this is obviously because it is easier to exceed your parents income when they started with a low amount, but absolute generational mobility is still strong. 75% of bottom quintile children make between 10 and 25 thousand dollars more than their parents

These numbers are interesting, but they need more context before we can fully characterize IGM.

How has intergenerational mobility changed over time?

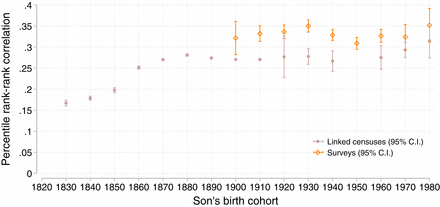

Relative intergenerational mobility has decreased significantly over the past 160 years. From a father-son income rank correlation of less than .2 in 1830, to one hovering at or above .3 today.

However, according to a 2020 paper from sociologists at the University of Pennsylvania most of this decrease happened before the 20th century began. “Intergenerational occupational rank–rank correlations increased from less than 0.17 to as high as 0.32, but most of this change occurred to Americans born before 1900. After controlling for the relatively high mobility of persons from farm origins, we find that intergenerational social mobility has been remarkably stable.”

This result is confirmed in a paper co-authored by Emmanuel Saez which tracks more recent trends in relative intergenerational mobility. They “find that percentile rank-based measures of intergenerational mobility have remained extremely stable for the 1971-1993 birth cohorts...children entering the labor market today have the same chances of moving up in the income distribution (relative to their parents) as children born in the 1970s.”

So relative IGM has decreased somewhat over the past century and a half, but this is due to huge structural changes in our economy that came from the mass urbanization and industrialization over the late 19th century. The high mobility of the 1800s was an exception to the otherwise relatively constant IGM levels, and the 20th century saw a return to the mean.

Absolute intergenerational mobility (The percentage of children’s households that out earn their parent’s households.) has seen a somewhat different trend. “Since 1880, the U.S. per capita gross domestic product has increased at an average of about 70 percent over each generation (roughly every 25 years)” again from Julia Isaacson’s paper. This strong growth trend continued well into the 20th century

“between 1947 and 1973, incomes roughly doubled. Since 1973, the increase over a generation’s time has been much smaller, about 20 percent. For this reason alone, upward mobility in recent decades has slowed” (everything changed in 1970)

A 2017 paper by Raj Chetty confirms this trend. He documents a dramatic fall in absolute income mobility “from approximately 90% for children born in 1940 to 50% for children born in the 1980s.” This fall is due to a combination of decreased GDP per capita growth, and an increase in inequality. There is less economic growth to raise children above their parents, and most of the gains go to people in the top quintile of income.

Other studies from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, however, show a reversal of this trend. The PSID follows families and the individual members and tracks several characteristics about them for 41 years from 1968 to 2009. When adjusting for changes in family size and inflation they find that

“Eighty-four percent of Americans have higher family incomes than their parents had at the same age, and across all levels of the income distribution, this generation is doing better than the one that came before it.” and that “Ninety-three percent of Americans whose parents were in the bottom fifth of the income ladder and 88 percent of those whose parents were in the middle quintile exceed their parents’ family income as adults.”

Absolute mobility has always been one of America’s best characteristics. Strong economic growth and geographic mobility have made for a dynamic economy whose rising tide lifts all boats. Despite the growing threats posed by slowdowns of economic growth and NIMBY-ist restrictions on dynamism and movement, absolute mobility is still quite strong in the US.

Despite what pundits on both sides of the aisle might tell you, America’s levels of either type of intergenerational mobility do not represent significant deviations from historical trends.

How does intergenerational mobility in the US compare to other developed nations?

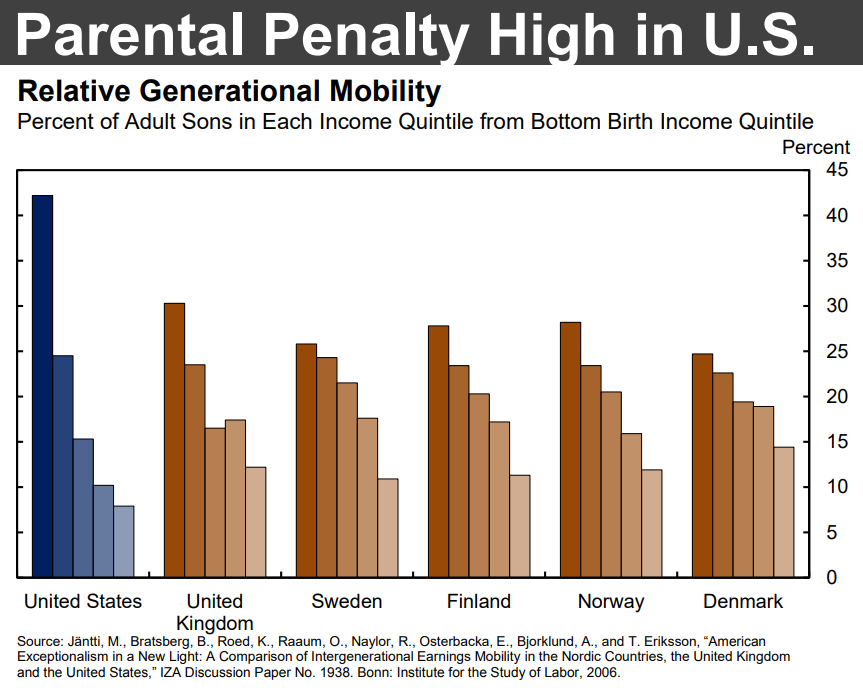

Relative IGM is much lower in the US than many other Western European nations and Canada

However, this difference is concentrated almost entirely in the bottom quintile of the income distribution. Relative intergenerational mobility in the top and middle quintiles is basically the same between all the nations in this sample

In other words, the parental penalty of having poor parents is especially high in the US, but the parental advantage from having wealthy parents is universal across nations with wildly different social safety nets, ethnic makeups, and economic cultures.

What about absolute mobility? This animated graph from Hans Roling gives a good overview of the global trends in absolute intergenerational economic mobility For most of the 19th and 20th centuries, the United States led the world in economic growth, and therefore in absolute intergenerational economic mobility. In the latter half of the 20th century, especially after 1970, there was a decrease in absolute economic mobility. By some measures, however, like the previously mentioned PSID study and this study from the Treasury department in 2007, absolute income mobility is still strong.

“Median incomes of taxpayers in the sample increased by 24 percent after adjusting for inflation [between 1996 and 2005]. The real incomes of two-thirds of all taxpayers increased over this period. Further, the median incomes of those initially in the lowest income groups increased more in percentage terms than the median incomes of those in the higher income groups. The median inflation-adjusted incomes of the taxpayers who were in the very highest income groups in 1996 declined by 2005.”

There is one recent paper out of Princeton that compares absolute intergenerational mobility across several OECD nations. It uses data and techniques from the 2017 paper by Raj Chetty above, which contradicts the results of the PSID measures of absolute mobility. The main results are in this graph:

However, In the appendix they produce the same graph but with controls for the changing household demographics (mainly the increase in single parenthood) to separate effects from family dynamic changes and actual changes in absolute income mobility. This control produces results that are much more consistent with the PSID data, and confirm a recent upward swing after a decline in the second half of the 20th century.

The United States does not stand out from other developed Western European nations by either measure of IGM (perhaps that is a failure in itself), except when it comes to mobility in and out of the bottom income quintile.

So what is causing this extreme immobility in the bottom quintile? Are levels of mobility comparable to those of Scandinavian nations enough or should we strive closer to the pure Equal Chance Economy model? How could we change intergenerational economic mobility if we wanted to? All of these questions and more will be asked and, hopefully, answered in Part II.