Is There Really a Child Penalty in the Long Run?

What this paper means for fertility

A couple of weeks ago three European economists published this paper studying the female income penalty after childbirth. The surprising headline result: there is no penalty.

Setting and Methodology

The paper uses Danish data that tracks IVF treatments as well as a bunch of demographic factors and economic outcomes over 25 years. Lundborg et al identify the causal effect of childbirth on female income using the success or failure of the first attempt at IVF as an instrument for fertility.

What does that mean? We can’t just compare women with children to those without them because having children is a choice that’s correlated with all of the outcomes we care about. So sorting out two groups of women based on observed fertility will also sort them based on income and education and marital status etc.

Successfully implanting embryos on the first try in IVF is probably not very correlated with these outcomes. Overall success is, because rich women may have the resources and time to try multiple times, for example, but success on the first try is pretty random. And success on the first try is highly correlated with fertility.

So, if we sort two groups of women based on success on the first try in IVF, we’ll get two groups that differ a lot in fertility, but aren’t selected for on any other traits. Therefore, we can attribute any differences between the groups to their difference in fertility and not any other selection forces.

Results

How do these two groups of women differ?

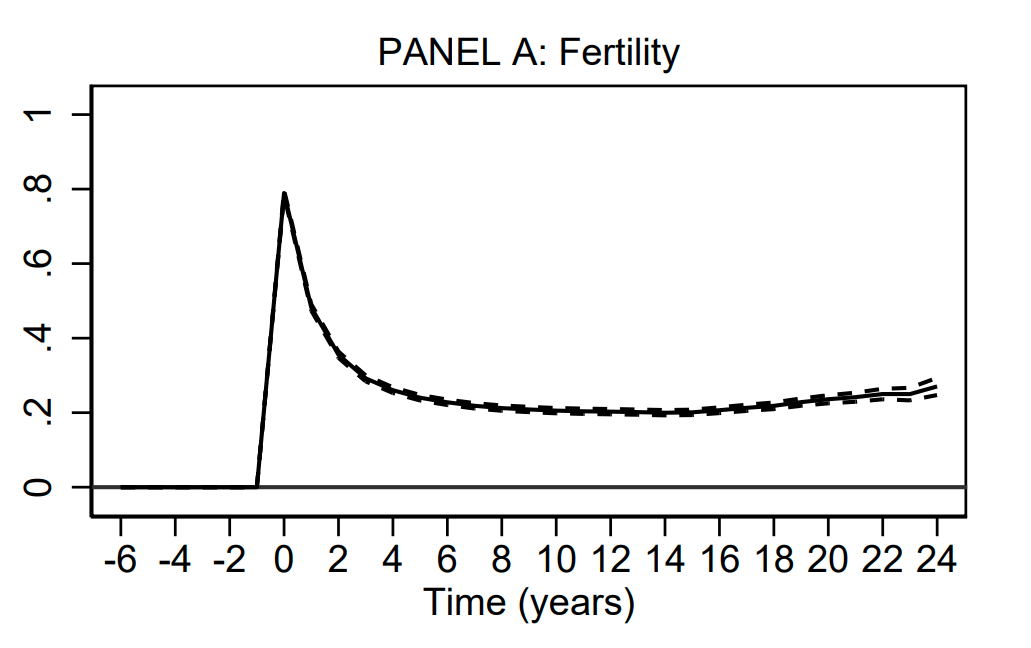

First of all, women who are successful on the first try with IVF are persistently more likely to have children. This random event causing a large and persistent fertility difference is essential for identifying the causal effect of childbirth.

This graph is plotting the regression coefficients on a series of binary variables which track whether a woman had a successful first-time IVF treatment X years ago. When the IVF treatment is in the future (i.e X is negative), whether or not the woman will have a successful first-time IVF treatment has no bearing on fertility since fertility is always zero; these are all first time mothers.

When the IVF treatment was one year in the past (X = 1), women with a successful first-time treatment are about 80% more likely to have a child that year than women with an unsuccessful first time treatment. This first year coefficient isn’t 1 because some women who fail their first attempt go through multiple IVF attempts in year zero and still have a child in year one. The coefficient falls over time as more women who failed their first IVF attempt eventually succeed and have children in later years, but it plateaus around 30%.

Despite having more children, this group of women do not have persistently lower earnings.

This is the same type of graph as before, it’s plotting the regression coefficients of binary variables that track whether a woman had a successful first-time treatment X years ago, but this time the outcome variable isn’t having a child, it’s earnings.

One year after a the first IVF treatment attempt the successful women earn much less than their unsuccessful counterparts. They are taking time off for pregnancy and receiving lower maternity leave wages (this is in Denmark so everyone gets those). But 10 years after the first IVF attempt the earnings of successful and unsuccessful women are the same, even though the successful women are still ~30% more likely to have a child. 24 years out from the first IVF attempt the successful women are earning more on average than the unsuccessful ones.

Given the average age of women attempting IVF in Denmark of about 32 and a retirement age of 65, these women have 33 years of working life after their IVF attempt. We can’t see their earnings that far out, but if we assume that the differences plateau after 20 years, the lifetime earnings of the first time successful women are about 2% higher (though the confidence interval includes zero).

Comparison to Previous Results

This is a huge change from previous results. You’ve probably seen graphs like this floating around twitter.

This is based off of an “event study” specification from this influential 2019 paper that also using Danish data. Why are the results from the instrumental variables design so different from these previous event studies and which results are more reliable? The 2024 IVF paper replicates these negative and persistent event study effects.

The authors argue for two reasons why their instrumental variables design is a more reliable measure than the event study.

First, the assumptions required for the event study to identify causal effects are stretched when trying to get at long term effects. Event studies compare women of the same age, education status, and profession but where one group of women has their first kid at a later age than the other e.g one at 28 and another at 30. This relies on an assumption that, conditional on all of these characteristics, age at first birth is random. There are very close parallel trends in earnings before first birth which lends some evidence towards this. Two or three years difference can conceivably be semi-randomly assigned e.g by matchmaking, but it is a bit hard to believe that women who have kids 10 or 15 years apart differ in only this respect, even with the 5 years of parallel pre-trends.

The groups of women defined by first-try success in IVF are more believably randomly assigned to having or not having a child, even decades after the treatment. These two groups also have the same coincident pre-trends in earnings that justify the event study.

Second, Lomborg’s 2024 paper finds evidence that women time their births to just before a wage growth plateau. The evidence it gives again comes from IVF failures. Women who were planning to have a birth, but never succeed, have much flatter wage growth after their planned birth year, even though they didn’t actually have any kids. So the divergence between childrearing mothers and non-childbearing mothers shows up even in this placebo case when neither group actually had kids. Therefore, the event study is overstating the earnings impact of childbirth.

This paper is also a bit inconsistent with an extremely similar paper by the same author from 7 years ago. This paper has the same methodology, the same setting, and the same data source, but has fewer years of data. It only tracks earnings to ten years out from the first IVF attempt. The author concludes finding “negative , large, and long-lasting” effects of childbirth on earnings. Quite different than the results in this more recent version. This reversal of results with longer data isn’t mentioned in the 2024 paper. The old version shows negative earnings effects persisting after 10 years while the new one shows the earnings effect at zero after 10 years. Even though both papers cover this period, they don’t match because the later paper has more cohorts ten years out, i.e the old paper only has 10 years of earnings data for women first trying IVF 1996-1999 but the new paper has 10+ years of earnings data for every cohort tracked in the IVF data 1996-2005.

What This Means For Global Fertility Trends

The authors don’t have any replication materials available as far as I can tell, the data probably has privacy protections too. One social science paper with no replication materials is not something you’d want to update on too much. The data and methods seem straightforward and solid. The main results hold up in a specification with no control variables which is good since there’s a lot of degrees of freedom when researchers can pick and choose which controls to include. Still, there could be massive fraud under the hood of this paper and it wouldn’t be that unusual so definitely take these results with a grain of salt.

If the results really are solid, there are also external validity concerns. We’d have solid results showing that childbirth does not have a lifetime earnings penalty for rich, middle-aged, Danish, otherwise infertile women, who chose to enroll in IVF. Denmark provides IVF for free for anyone a doctor says is infertile. Denmark has some of the most generous parental leave policies in the world and a highly gender-equal labor market. Older and otherwise infertile women are more established in their careers, have already completed education, and plan their births. All of these differences and more threaten the generalizability of these results.

If the paper does generalize, even just to rich western women, it would be an important change to existing models of fertility decline. On the one hand it’s good news. It’s further evidence that the opportunity cost of childbirth is not an insurmountable barrier to combining high fertility and high incomes. On the other hand, fertility in Denmark is still very low and falling. If fertility is falling even though mothers don’t have to sacrifice returns from their career, then economics is not the main motivator of that trend. Instead, it’s a deeper cultural trend which is much more difficult to amend with policy.

This is interesting and important research and I hope to see replications and generalizations in the future!

I don't think that an exclusive focus on women who can afford to do IVF and also who choose to do it is sensible. Most babies are going to be born without IVF for a long time. Is this paper trying to claim that there is on motherhood penalty for anyone?

"If fertility is falling even though mothers don’t have to sacrifice returns from their career, then economics is not the main motivator of that trend."

This doesn't make sense.

The conventional wisdom was (and probably still is) that there *is* a motherhood penalty. There's no reason to think that these actually women know whether or not they'll have to sacrifice returns from their career, right? So that statement is incorrect.