Jane Jacobs Can Fix American Cities, Even Though She Helped Break Them

American cities are dysfunctional. Housing costs now absorb nearly all the economic surplus that used to spread prosperity in exchange for old, small, and often ugly housing. Large swathes of our cities are enervated by parking, highways and stroads. Public transit infrastructure is lacking and hasn’t significantly expanded in decades. Attempts at constructing more have sucked up decades of time and billions of dollars. American cities also have aberrantly high rates of crime, traffic deaths, homelessness, and drug use.

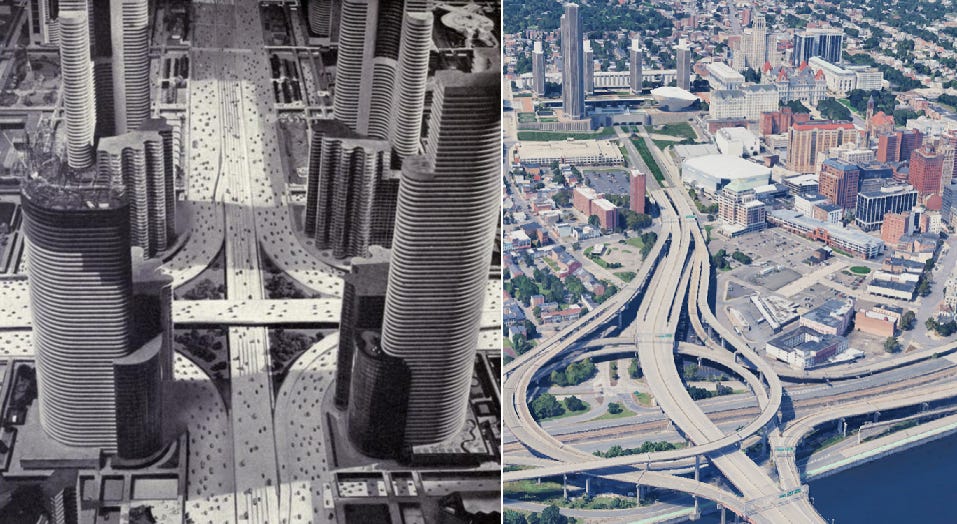

Popular political tracts like Abundance or Why Nothing Works explain American urban history as swings of a pendulum. On one end, you have Robert Moses and the high-modernist, ultra-state-capacity of the early 20th century. Comprehensive zoning codes were invented and spread, entire neighborhoods were demolished with little recompense, and super-highways were built in their place. On the other end of the pendulum is Jane Jacobs and the political and social movements of the 1970s that enshrined local participation and veto, environmental consciousness, and bureaucratic process as defenses against slum-clearing urban renewal. Both of these movements went too far and left their scars on American cities so a new path between the two extremes is needed.

This story correctly identifies the two major sources of the problems facing American cities: the destructive overreach of modernist urban renewal and the paralyzing vetocracy of environmental review. But it wrongly portrays Jacobs as a champion of the latter problem. In fact, a careful reading of "The Death and Life of Great American Cities" reveals that Jacobs didn't advocate for preservation and obstruction (at least, not in the book itself)—she advocated for market urbanism and organic development. The solution to our urban problems isn't a middle path between Moses and Jacobs, but rather a return to Jacobs' actual ideas, not the distorted version that became embedded in planning practice.

The first pendulum swing: High Modernism or the Radiant-Garden-City-Beautiful

High modernist urban planning shaped the urban form of American cities in two main phases.

The first phase, in the early 20th century, began with the invention of comprehensive zoning codes and density regulations. Planners like Edward Bassett and Ebeneezer Howard saw rapidly growing industrial cities, with high density tenements and overlap of residential, commercial, and industrial land uses, as threats to nature, health, light, and clean air. They wanted to separate land uses and spread out the population as much as possible. Here’s Edward Bassett in New York City’s 1916 comprehensive zoning plan:

Most of the evils of city life come from congestion of population. In precisely the measure that the city’s population can be distributed will those evils be mitigated.

It is therefore essential in the interest of the public health, safety, comfort, convenience and general welfare that a housing plan be adopted that will tend to distribute the population and secure to each section as much light, air and relief from congestion as is consistent with the housing of the entire population for a considerable period of years within the areas accessible and appropriate for housing purposes.

The height restrictions, setbacks, and exclusive, single-use zoning codes that these planners championed are still common in every major American city today.

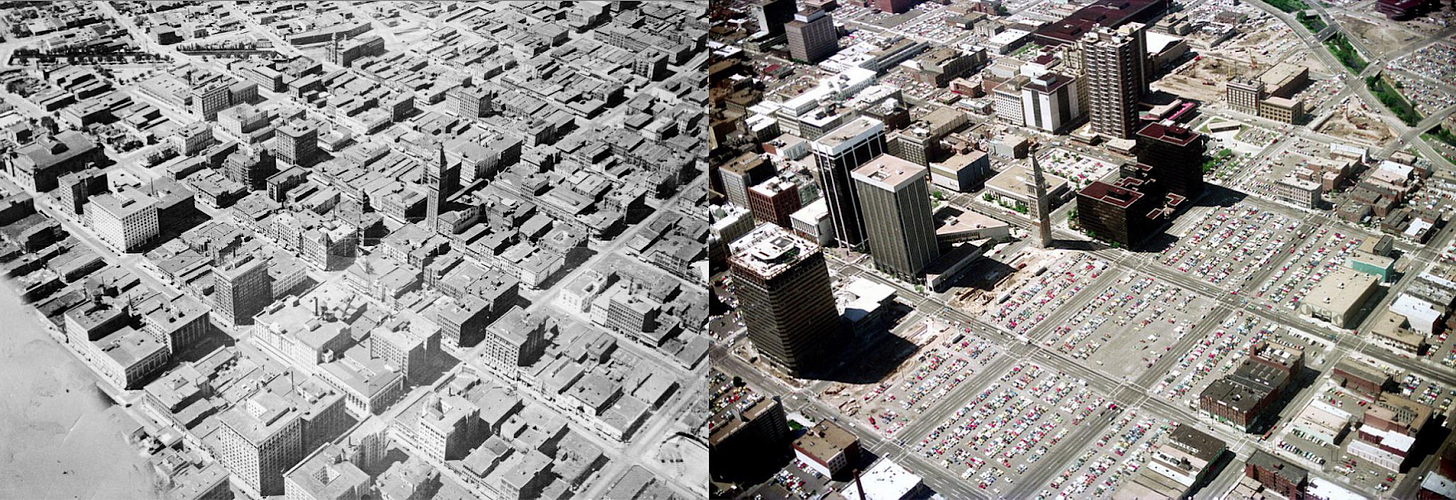

The second phase of high modernist urban planning, called urban renewal, happened closer to the middle of the 20th century after the automobile grew to dominate transportation. This phase maintained the top-down control of private land uses and the goal of de-densifying urban areas with suburbs, but it added a focus on automobile traffic management and ambitious construction of public housing and infrastructure. While the first phase placed legal restrictions on new development and grandfathered in older buildings, urban renewal demolished wide swathes of older neighborhoods and replaced them with highways or copy-pasted high-rises surrounded by roads, parking lots, and open space.

High modernist urban planning was a massive mistake. The de-densifying mission of the first phase sabotages the labor market agglomeration benefits that make cities productive. The restrictions placed on city population by those early 20th century regulations have lowered US GDP by 8-36%, potentially tens of thousands of dollars per person. The second phase of high modernism was somewhat more compatible with a dense labor market concentration since high-rise public housing can be dense, but it destroyed the dynamic street life that makes cities interesting and safe while heavily subsidizing car transport and suburban development. The push of urban crime waves and the pull of cheap single-family housing with subsidized transport and parking emptied city centers into the suburbs. Both phases of high modernism fastidiously segregated land uses (and people), leaving cars as the only option to get from one's house to stores or work.

The swing back: Jane Jacobs, Rachel Carson, and Sherry Arnstein

Criticizing high modernism is completely mainstream within urban planning today. The swing of the pendulum away from the practices of urban renewal began in the early 1960s with the most lauded urban planning book of all time, The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs, which is self-described as an “attack on current city planning and rebuilding,” (current in 1961).

Jane Jacobs’ critique was subsumed into the larger 60s and 70s activist movements against high modernism including environmentalism and civil rights. “Highway revolt” protests and community meetings across the country, some of which were organized by Jacobs herself, elevated local public participation as the best way to practice democracy. In San Francisco this strategy successfully protected the city from an intra-city freeway. This process of public input was then formalized into discretionary review, which allows agitating San Francisco residents to prevent development even when it conforms to all local zoning codes. Later in the 70s, California wrote a public-hearing right for all landowners who might be affected by a development project into its constitution. Similarly, after a protest movement against public housing in Forest Hills, Queens, New York City devolved power over local zoning and land use to community boards which became “the first line of defense in New Yorkers’ war against growth.”

Jacobs’ arguments were quickly swept into the larger flood of support for formalizing participatory democracy that began in the 1960s. In 1965, The American Institute of Planners published Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning by Paul Davidoff, which advocated for establishing “an effective urban democracy, one in which citizens may be able to play an active role in the process of deciding public policy” and that “great care must be taken that choices remain in the area of public view and participation.” Around the same time, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation were published, further catalyzing the environmental movement and making a case for far more public participation in government decisions. The slew of procedural environmental laws which followed, like NEPA and the National Historic Preservation Act, were enthusiastically incorporated into urban planning.

These laws have preserved the mistakes of high modernist planning and added their own constraints to successful urbanism. Public hearings on zoning changes essentially locked in the exclusionary, low-density zoning codes set in the early 20th century. A small population of incumbent homeowners can shut down upzoning of single-family districts even in the most valuable urban land on earth. Procedural environmental laws locked in the car-centric urban forms built by Robert Moses and his ilk. High-speed rail, subway extensions, even bus lines and congestion pricing projects are delayed by years and inflated by millions due to costly environmental review. Environmental law constraints have made even the few successes of mid-century urbanism, like Sea Ranch California, impossible to replicate or extend today.

Planners bet big on devolution of power, public participation, and environmentalism rather than deregulation and market urbanism. They agreed with Jacobs that the Robert Moseses of the world shouldn’t be able to eminent-domain entire neighborhoods and run big highways through the city, at least not without democratic approval and procedural review. So construction projects have to be preceded by public comment periods, town meetings, and environmental reports.

Veto power was distributed outside of city governments, and planners successfully avoided another mistaken urban renewal, but they did so by demolishing our capacity to build anything at all.

Jane Jacobs’ rules can fix American cities

In manifestos like Abundance or Why Nothing Works, this is where the story ends. Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs are opposite paragons of their respective philosophies and modern policy makers must chart the narrow way between. While this is a useful prescription for how to move on from the legacy of environmental proceduralism and urban renewal, it’s not an accurate portrayal of Jane Jacobs’ views.

In “Death and Life” Jacobs argues that urban planners should plan less. They should stop drafting grand visions and bulldozing neighborhoods to rebuild them in their image. “Public policy can do relatively little that is positive to get working uses woven in where they are absent and needed in cities, except to permit and indirectly encourage them.” When discussing a successful commercial district in Nashville she notes that “Nobody could have planned this growth. Nobody has encouraged it.”

Even the most widely supported uses of urban planning, like setting maximum densities and separating residential and industrial land uses are criticized. “What are the proper densities for city dwellings?” she asks, “The answer to this is something like the answer Lincoln gave to the question ‘How long should a man’s legs be?’ Long enough to reach the ground.” On industrial pollution control she says “Of course reeking smokestacks and flying ash are harmful, but it doesn't follow that intensive city manufacturing (most of which produces no such nasty by-products) or other work uses must be segregated from dwellings. Indeed, the notion that reek or fumes are to be combated by zoning and land-sorting classifications at all is ridiculous. The air doesn’t know about zoning boundaries. Regulations specifically aimed at the smoke or reek itself are to the point.”

In Jacobs’ view, planners should merely set favorable conditions for decentralized, unplanned, and incremental development. Lay out the street grid if you must (though with smaller blocks than Manhattan) and bring the infrastructure to where it’s needed but otherwise refrain from regulating private land use. Let all the uses of the city mingle together and fill each street with eyes and activity at all times of the day. Jacobs is like Hayek (1945) or The Fatal Conceit applied to urbanism. “The curious task of economics [and Jacobsian urban planning] is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.”

Jacobs does advocate for more local city government and praises public participation in planning meetings, but many of her reasons for wanting more devolved power in city planning were good. Far away bureaucracies can’t transmit the man-on-the-spot knowledge that planners need to support organic development. Bureaucracies have other familiar problems as well: “In Baltimore a sophisticated citizens group engaged in conferences, negotiations, and a series of referrals and approvals extending over an entire year — merely for permission to place a sculpture of a bear in a street park!”

The pendulum swings between overbearing state capacity and sclerotic vetocracy created massive problems that are still causing problems a century later. But the path to redemption can be found in the already canonized works of Jane Jacobs.

Jacobs proposes four ingredients that make a vital city, district, or street.

The district must serve more than one primary function; preferably more than two.

Most blocks must be short; that is, streets and opportunities to turn corners must be frequent.

The district must mingle buildings that vary in age and condition.

There must be a sufficiently dense concentration of people.

Each of these four rules is phrased as a positive obligation. This leads to some confusion where people will try to plan a Disneyland Jane Jacobs urbanism where all of these qualities are built in from the top down. Jane Jacobs Disneyland is surely better than Corbusier’s towers in the park, but that kind of new urbanism is not the solution to the problems with American cities. As Jacobs says “A city cannot be a work of art.”

Jacobs’ four positive obligations can actually be compressed down to two rules.

Don’t regulate land use on private plots.

The density and mixed uses called for in obligations 1 and 4 are fulfilled automatically when urban planners do not artificially separate land uses and reduce density. Let diverse, mixed uses and high densities arise where they may in cities. If extreme negative externalities result, address them case-by-case rather than through blanket zoning.Encourage incremental development and infill.

The dynamic street patterns and varied building ages called for in obligations 2 and 3 also arise naturally when cities develop incrementally, rather than in giant lurches as new neighborhoods are demolished and built all at once. Let winding streets with frequent breaks and wide-ranging building ages emerge naturally as developments stack up in an unplanned, organic pattern. This means lowering the regulatory fixed costs of development so that small projects can arise easily, and abandoning master plans.

These rules have already found success in the wonderful urbanism of Tokyo. Land use regulations there are much laxer, especially for commercial shops and restaurants, so the residential and commercial density of the city is high. That means cute apartments surrounded by a walkable community of shops and restaurants are cheap and abundant. Incremental infill development is common and easy to do in Tokyo, so there is a combination of modern and classic architecture and a range of price points that support diverse uses for each street in the city. Tokyo doesn’t have a gridded street plan and the emergent pattern creates lovely neighborhoods with short blocks, alluring alleys, and shielding from cars.

These rules also created many of the most charming neighborhoods in urban America. Boston’s North End, New York’s Greenwich Village, and D.C’s Georgetown were all largely built before comprehensive zoning codes and are full of buildings and shops that would be illegal to build today.

There are problems with American cities that aren’t addressed by these rules. To get better transportation infrastructure, you have to address environmental proceduralism for public projects as well as private ones. More city streets that are active throughout the day would help with public order and crime, but when the social order enforced by crowds of onlookers is not backed by credible force from local police, open homelessness, drug use, and crime can persist even on the busiest streets.

But these two principles are necessary steps on the path towards embracing Jane Jacobs’ ideas, if not her advocacy, and redeeming the major mistakes of urban planning.

Good read! Yoni Appelbaum writes about Jacobs at length in Stuck. While its clear that many learned the wrong lessons from her work, it seems she did, too. Her activism on behalf of historic preservation halted incremental development in her own neighborhood, which then metastasized across New York through historic districts. So, if history misrepresents Jacobsian Thought, it's in part because of the legacy of Jacobsian Action.

There is an epic takedown of her in Yoni Appelbaum's book Abundance. She basically wrote the NIMBY advocacy playbook.