New Results on Fertility and Growth

Should we believe them?

Last month Serhan Cevik, a senior economist at the International Monetary Fund, published a working paper studying the causal effect of fertility rates on economic growth. Hat tip to Lyman Stone for alerting me to this paper’s existence and luring me in with the clickbait title:

A positive relationship between fertility and economic growth is intuitive. People are the most important input to every production process (for now). People come up with the technology and ideas that fuel economic growth. People specialize and trade with one another and the more people there are, the deeper and more productive this specialization can be.

On the other hand, rising opportunity costs, quantity-quality tradeoffs, and other cultural/religious changes have decreased fertility as incomes have risen. These effects are strong enough that the simple correlation between economic growth rates and the change in fertility rates is highly negative.

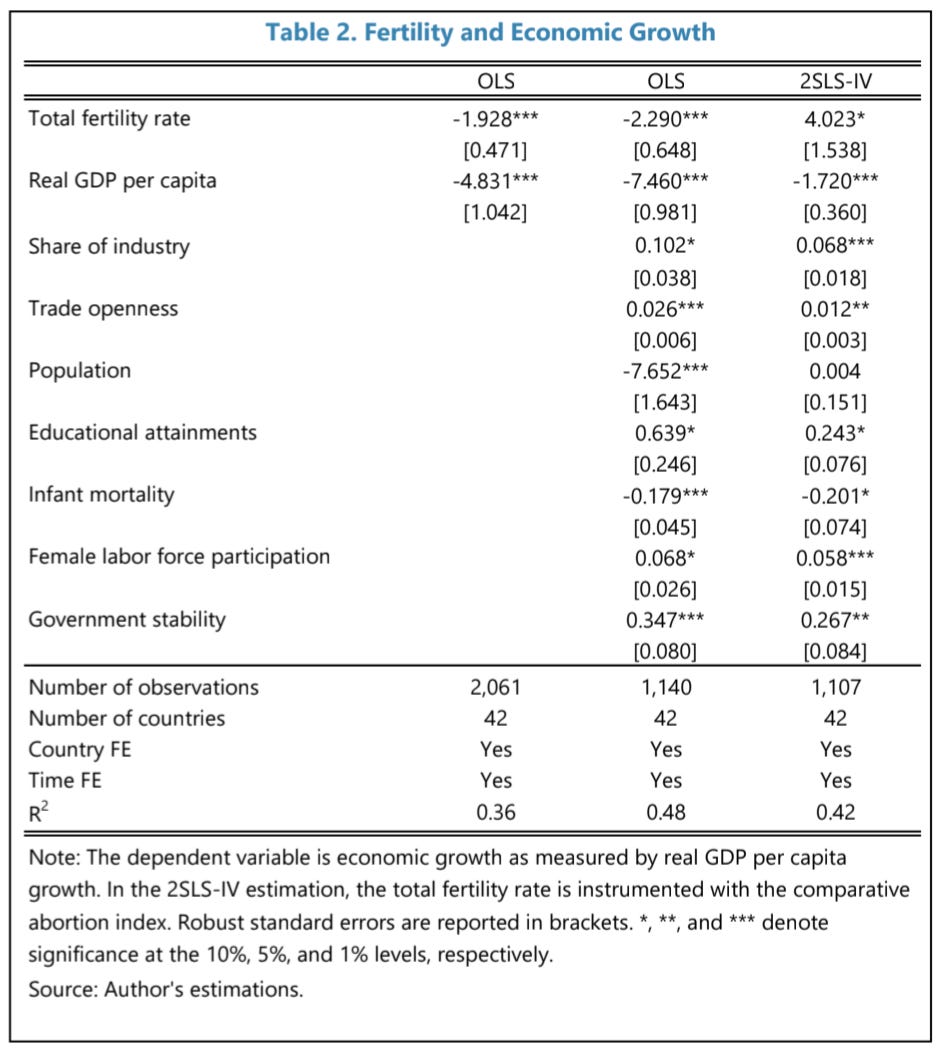

All of these relationships are supported by economic theory and some aggregate empirical research, so what does this new paper bring to the table? They claim to have a unique causal identification strategy using an instrumental variable.

Here’s what that means: if you just sort countries by their fertility rates, you’ll also end up sorting them by all the other things that determine fertility, which might have their own effects on growth. So if you find that high fertility countries have lower growth rates, you have no way to tell if that’s due to fertility itself or due to the religiosity, patriarchy, or poverty that’s causing the high fertility rate. If there’s reverse causality and GDP growth lowers fertility, then sorting countries by fertility rates also sorts them by GDP growth rates and any effect you find between the two is meaningless.

What you need is some way to sort countries into groups that differ in fertility rates, but not in any other ways that are relevant to GDP growth rates. The authors of this paper propose abortion policy as a sorting method.

It's easy enough to show that countries with different abortion policies do have very different fertility rates. But that second condition — that countries which differ in abortion policy don't differ in any ways that affect growth other than fertility — seems obviously wrong.

Countries with strict abortion policies are more religious, less “western” (in this sample, more Muslim), more patriarchal, possibly less democratic, etc. All of these things are contributing their own effects to the growth differences between strict and liberal abortion countries but the author’s identification strategy attributes everything to fertility differences. I would be surprised if the difference in abortion numbers even comes close to explaining the difference in births between nations, so there must be some other varying factor.

The authors can address this somewhat with control variables, e.g for educational attainment or female labor force participation.

They also run a specification where they separate “advanced economies” and “developing economies” and find a smaller, though still significant and positive sign-flipped effect of fertility on economic growth. These results make their claim slightly more believable, but if my prior wasn't already that fertility causes economic growth, I don't think this evidence would be satisfying.

I'm already confident that global fertility decline will drag down economic growth, but higher quality economic research on precisely how much growth we should expect to lose would bring the issue into focus for policymakers. Unfortunately, Cevik’s paper doesn't fit the bill.

These results are counterintuitive except for agrarian economies where child labor is a significant input to production. Generally, children are an inferior good; that is, family size decreases as income rises. This looks like a statistical artifact. Are the data and statistical analyses available to the public?

FWIW I concur it’s fairly weak evidence.