Olympic Charter Cities

Hosting the Olympics is expensive and becoming unpopular. Tens of billions of dollars are spent by each host building extra athletic venues, accommodation and transportation for tens of thousands of new guests, and a media production complex to house the IOC (International Olympic Committee) broadcast team. This has made the Olympics less appealing to host, and fewer cities are bidding. The reluctance of traditional host cities opens an opportunity for a public-private partnership development of an Olympic village charter city. After the Olympics are over, this private village could act as a special jurisdiction aimed at economic growth and a sustainable approach to the Olympics.

The costs of hosting the Olympics are high and have been increasing over time. The 2000 Olympics in Sydney cost seven billion dollars while the 2014 Sochi Olympics cost more than fifty billion. Tokyo 2020 has already cost over fifteen billion dollars and will likely reach twenty billion before it is over. Along with rising initial investments, cities face challenges in redeveloping their Olympic construction projects into economically productive areas after the games. Situations like the squatter city in Italy’s Turin village and the dilapidated apartments from Rio 2016 are a constant drain on municipal budgets and are not uncommon among host cities.

Additionally, the delay of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics connected with the likelihood of endemic disease has made hosting throngs of international spectators a more dangerous proposition. Although the Olympics are still the world’s most popular spectator event, these rising costs have sapped institutional interest in hosting the Olympics. Consequently, the bids for next three summer Olympics (Paris 2024, Los Angeles 2028, and Brisbane 2032) were all decided with no contest; the cities that won were the only ones that bid.

A public-private partnership model for building the Olympic village would alleviate some of the budgetary pressure on governments and provide a launchpad for stakeholders to get their special jurisdiction off the ground. The current funding model for Olympic projects is that governments foot the entire upfront bill and pay for private contractors to build the stadiums and a mini-city. In exchange, they don’t share the revenue from the games themselves or the developed area after the games with anyone (except the IOC). Sometimes this model works fine, as with London’s 2012 Olympic village, which was built by private contractors and converted into a square mile of upscale residential development, now called the East Village.

Frequently, however, unexpected costs outstrip revenue from the games and the area developed for the Olympic city falls into disuse. Even London’s East Village was eventually sold to developers at a 275 million pound loss.

An Olympic charter city provides an alternative funding model that has the potential to be more profitable for cities and private developers. As in the development of a charter city, a portion of the upfront cost of construction would be paid for by a private developer, rather than entirely from the local government. This cost sharing is mirrored after the games where the local government and a private charter city developer share political autonomy, tax revenues, and the cost of providing public services for the Olympic charter city. Governments benefit from this partnership because shared upfront costs will make it easier to sell Olympic hosting plans to short-term oriented political stakeholders and taxpayers, and it will mean larger profits from TV licensing deals with the IOC. Governments also avoid the scandal of wasted resources and disused Olympic construction by promoting long term economic dynamism through the political and economic reforms of the post-games charter city. Private developers will have to invest more upfront, but they will get a stake in a economically dynamic, politically autonomous charter city with lots of pre-built infrastructure next to an existing international city. Additionally, this charter city will be advertised to billions of people across the world during the games, ensuring that it does not go unnoticed.

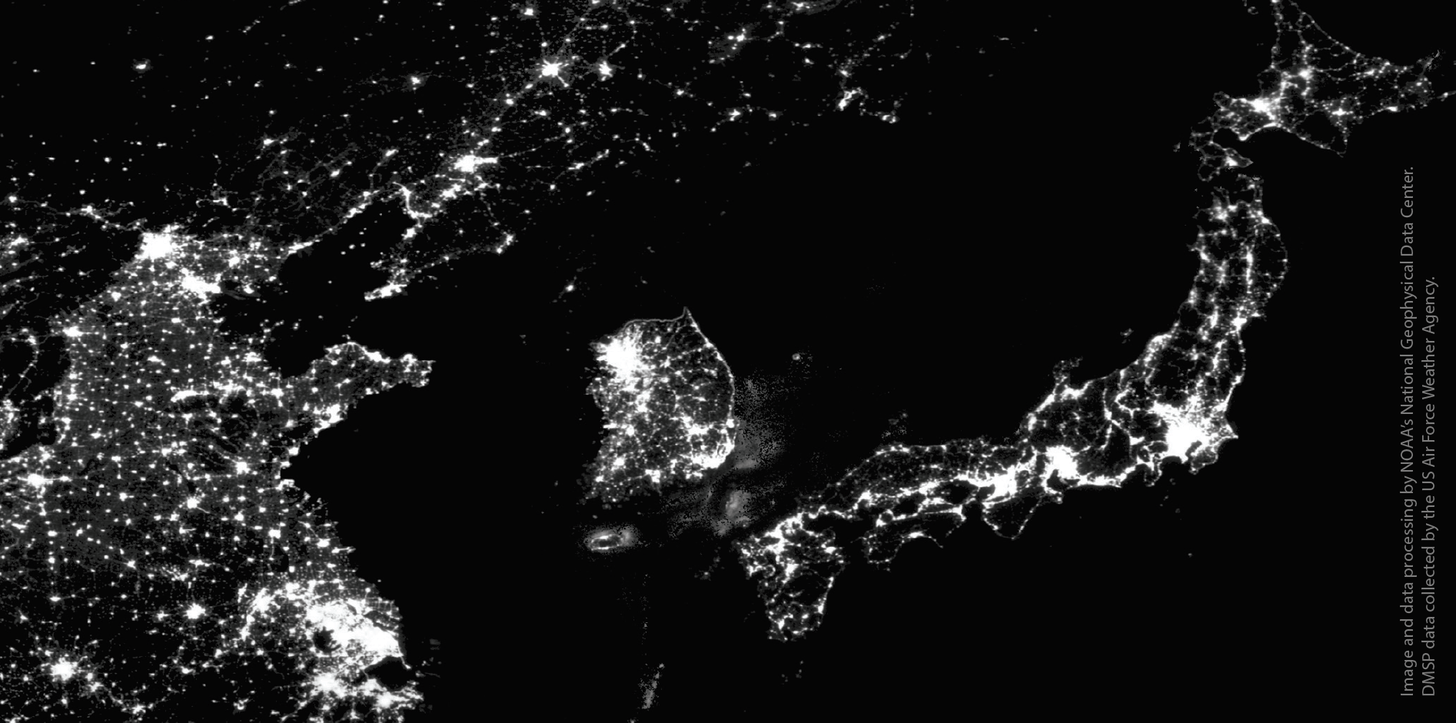

The argument for the economic potential of an Olympic charter city is the same as for any charter city. Institutions are the foundation of economic growth. North and South Korea have essentially the same geography, history, and culture but they have radically different levels and rates of economic growth. This is because they have very different institutions. South Korea has solid private property rights, an independent court system, democracy, and free trade, while North Korea is a communist dictatorship.

Charter cities are a way to improve institutions. They can do this in multiple ways. First is through capacity building. This is most relevant in underdeveloped countries where existing governments are underfunded, poorly run, and unable to provide government services. A charter city would employ international expertise in logistics and be forced to provide cheap and high quality service by the profit motive and competition. Charter cities can still advance economic growth in a highly developed country with a competent government, however. The second way charter cities can improve institutions is by providing a set of rules that streamline regulations, promote international investment, and decrease tax burdens on business. This path to economic growth through liberalized special jurisdictions has brought dozens of nations out of extreme poverty. Finally, charter cities provide a laboratory to test new ways of organizing society. For most of human history, the only way to experiment with a new form of government was war, revolution, or colonization. All extremely costly and coercive experiments. Charter cities can experiment at low cost and without coercion because the city is a nimble political unit and everyone opts in to living there. Olympic charter cities do not differ from the general model of creating economic growth through institutional reform. Rather, they aim to fill a gap in an existing source of city-scale construction projects which are becoming less popular and less viable through traditional funding models.

There are significant challenges in carrying out this plan. Foremost is collecting the requisite financial and political capital to host the Olympics and create a charter city. Olympic proposals are often met with widespread public backlash, and the frequent cost overruns of Olympic construction projects may shy away some private investors. Although special economic jurisdictions are becoming more common, charter cities are still a new idea so getting governments and voters on board will be difficult. Another issue is the long timescales that Olympic plans operate on. The winners of an Olympic bid are decided eleven years in advance, but proposal planning must begin years before that. Carrying a construction master plan and city charter through multiple governmental regimes requires lots of commitment and focus from a large team of builders and politicians. Importantly, however, none of this makes creating an Olympic charter city much harder than hosting the Olympics or creating a charter city was already. Hosting the games already requires decades of planning, multi-billion dollar investments, and bipartisan political buy-in. Charter city proposals have already stretched between opposing political regimes, defended against negative public opinion, and invested large sums of money. It makes sense to combine these ideas because they share a lot of the fixed costs of financial and political capital. Tax sharing agreements and Olympic advertising also help internalize some of the externalities of public goods provision. Creating an Olympic charter city will not be easy, but neither part of the idea was easy to begin with. Combining the ideas allows both parties to benefit by trading the costs and benefits of the Olympics and charter cities across time.

The IOC has made repeated commitments to the sustainability of the Olympics in the face of scandalous reports of monumental waste and pollution from many of their events. Olympic charter cities provide an opportunity for them to fulfill the sustainability goals that they have openly committed to. Creating charter cities in place of abandoned Olympic villages would help avoid some Olympic waste, but the bi-annual pace of Olympic construction projects may be too fast for demand to keep up. The ultimate solution to the waste of building yet another aquatics center is to have a permanent Olympic city. There may have to be separate locations for the two seasons or even a pre-defined circuit of cities, but selecting a new city each year is the true source of Olympic waste. An Olympic charter city is the perfect place to house such a venue. It would be a truly international city; not entirely governed by any sovereign so the IOC doesn’t have to pick favorites. It would reuse stadiums and media centers to fulfill sustainability goals, and it would become a premiere tourist destination for the entire world as the periodic influx of Olympic spectators draws in world class entertainment and amenities.

As the costs of traditionally hosting the Olympics rises ever higher, the arbitrage opportunity for an Olympic charter city grows. Whether Olympic charter cities are an addition to the existing city-switching model of the Olympics, or the basis for a more radical change, they will save governments money on upfront costs, reduce wasted infrastructure, and promote economic and institutional growth.