Should We Have Kept The American Empire?

Arguments Against Renouncing Empire

It’s late August, 1918. Woodrow Wilson is in the middle of his second term and over the next hundred days the German lines on the western front of WW1 will buckle under the weight of nearly 2 million fresh American troops.

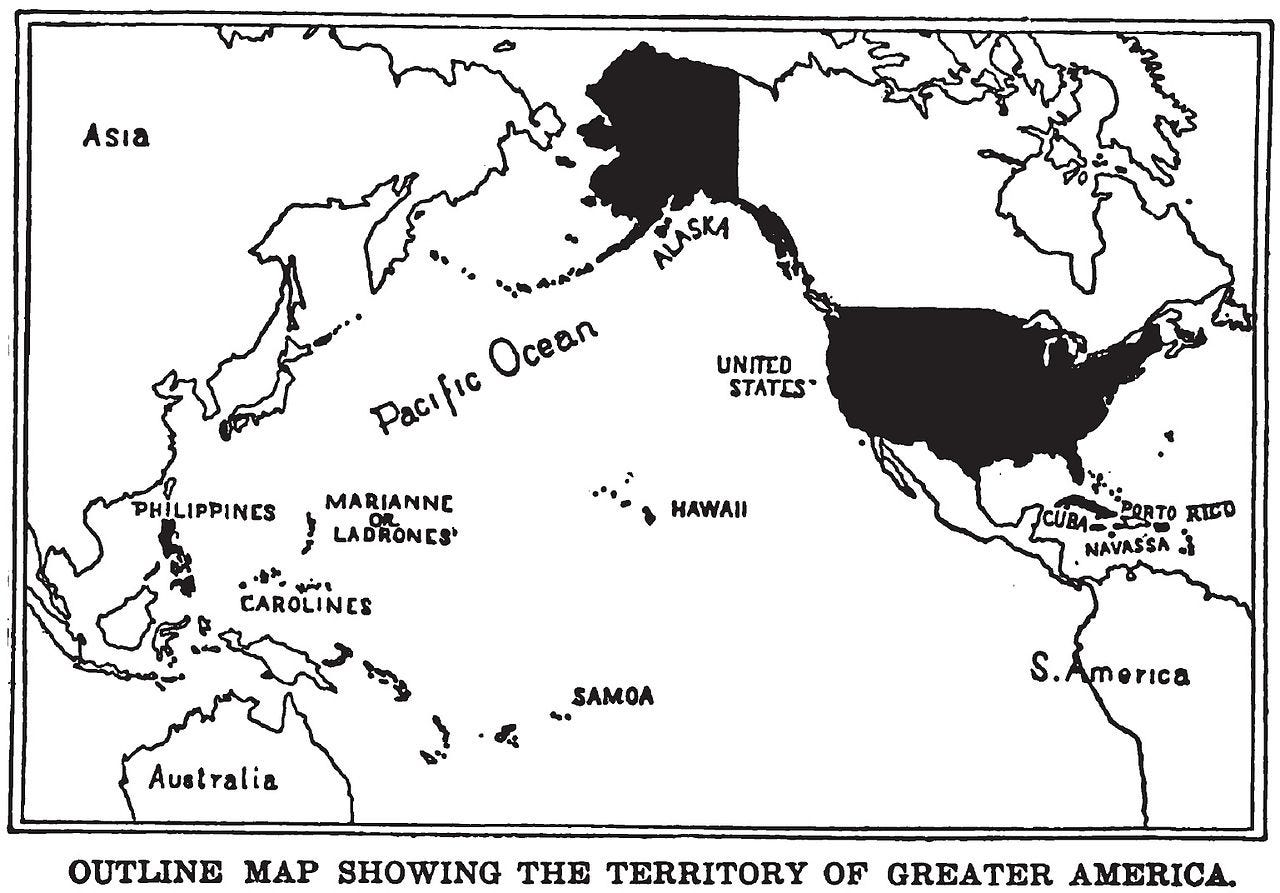

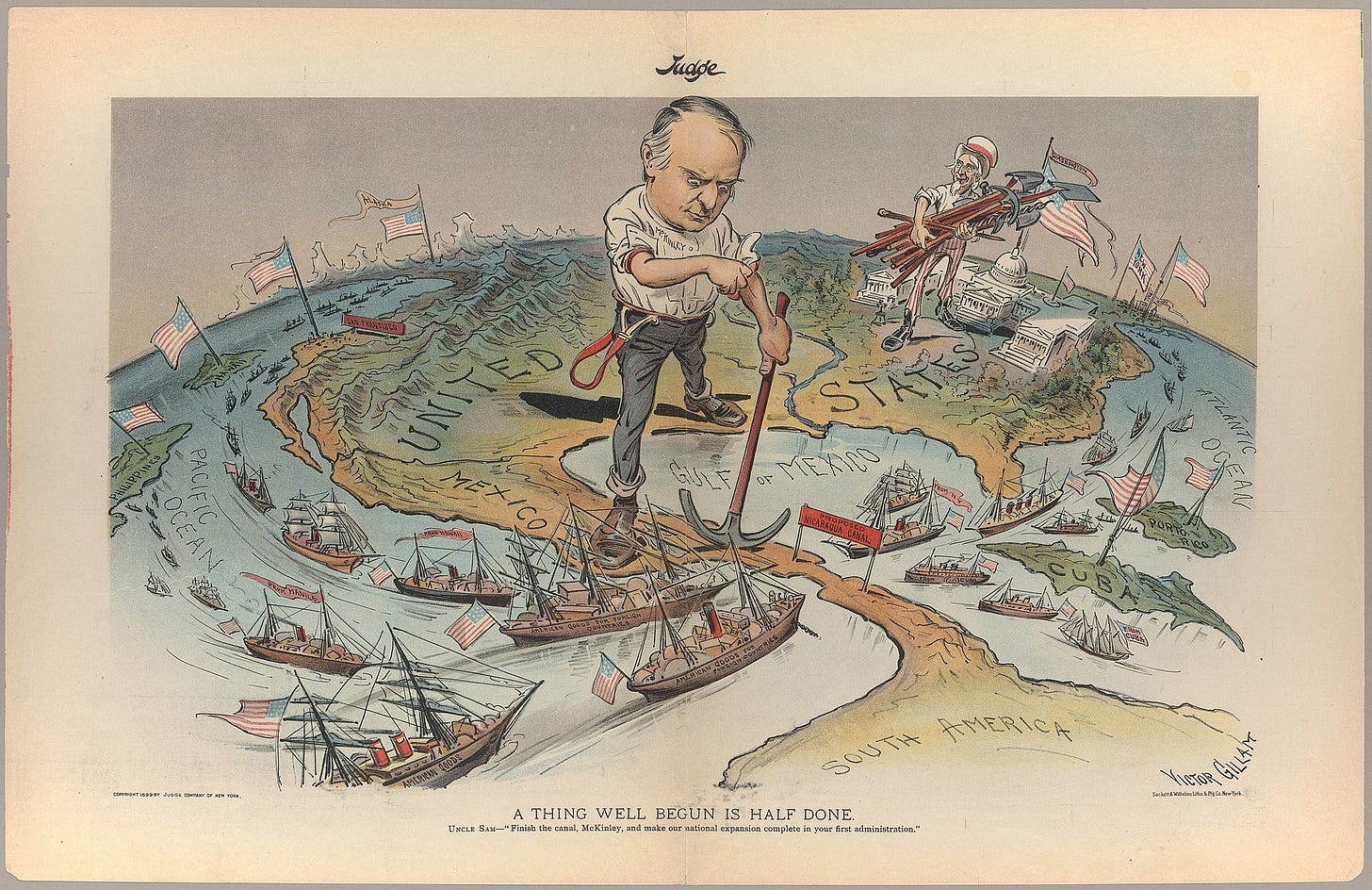

Elsewhere on Earth, the United States is at its greatest territorial extent. Manifest destiny stretched the nation from coast-to-coast half a century ago and Seward’s Folly no longer looks like a mistake. America has held on to the territorial gains it made in the Spanish-American war, including Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines, and somewhat less directly, Cuba. Simultaneously, the US hoovered up Hawaii, Samoa, Midway, and around 50 other smaller islands in the Pacific from former Spanish, German, and British colonial possessions. 15 years ago, in 1903, the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty established the Panama Canal Zone under direct American control. 11 years later, the canal was complete.

Most recently, European threats to Monroe’s exclusive claim over the New World, capitalist interests in Caribbean investment, and Woodrow Wilson’s paternalistic desire to make the world “safe for democracy” have led to de facto military control of Hispaniola, Cuba, and Nicaragua. Combined with the recent purchase of the Virgin Islands from Denmark, the Caribbean is essentially an American lake.

Over the next several decades, America will relinquish many of these holdings and shrink to her current size. The question is: Was this shrinking good? Was it right for the US to give up the territory it once held?

General Arguments Against Renouncing Empire

Note that the question of whether the US should have relinquished its maximum territorial extent is different than the one facing America in 1865 or the question of expanding American borders today. There, you have to consider the substantial costs of actually conquering territory in war. Holding on to land already conquered is less costly than conquering anew.

Nonetheless, there can be large costs to holding territory as the often horrifying history of colonialism shows. So isn’t it obvious that American imperialism was a mistake, and thus that it was good that the US eventually backed off?

The first thing to notice when considering this question is that America did not actually give up all of its imperial conquests. Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, a smattering of pacific islands, Alaska, and arguably even much of the American Southwest are spoils of conquest or purchase.

No one seriously considers giving up any of the pieces of our imperial history that we kept. The Hawaiian independence movement is perhaps the most popular, but that sets a low upper bound. This acceptance of the pieces of empire we retained suggests that if we had kept more of our 1918 peak territory, people would accept those additional pieces just as easily today.

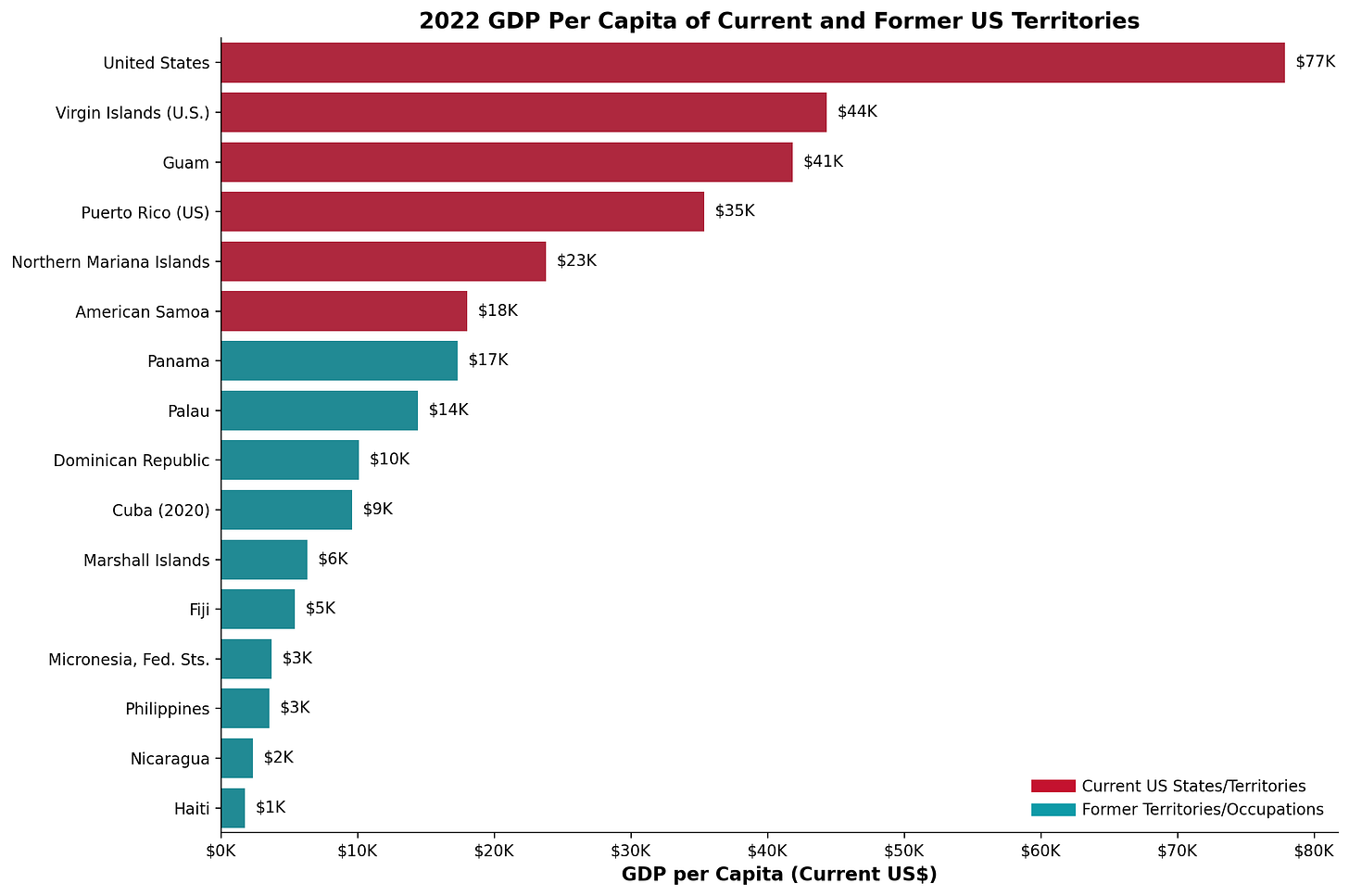

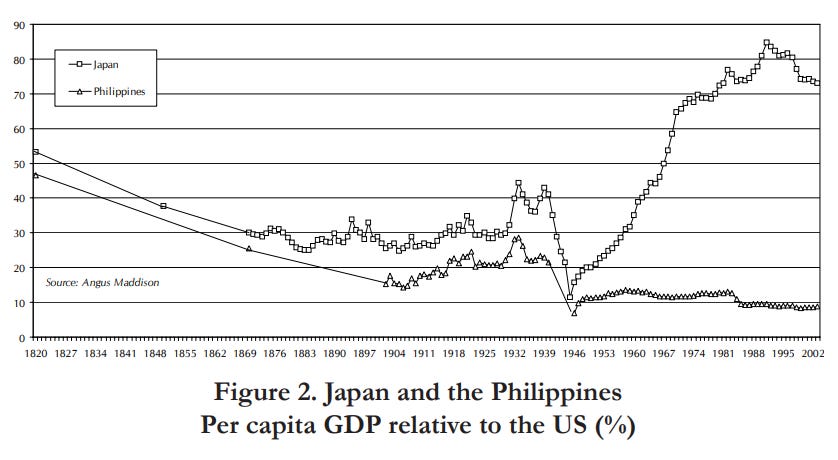

Reluctance to give up what we kept isn’t just status quo bias. The economic performance of the states and territories still within the US compared to the nations we let go is evidence that American annexation has large positive effects. The causal inference in the opposite direction is even more intuitive: how much poorer would Hawaii become if it were cut off from the American economy, immigration, and institutions? More precise causal inference on the positive economic effects of American annexation is available here.

Another argument against renouncing empire flows from a belief in the benefits of free trade and immigration. I won’t argue for this belief here, only note that the division of labor, and thus the prosperity of an economy, is limited by the extent of the market. But given a belief in these benefits, territorial expansion looks better. Integration under the same national umbrella seems like about the only way to sustain and spread free trade and immigration. The US can’t even manage it with Canada. The principal domestic supporters of Philippine independence, for example, were American farmers who didn’t want to face competition from tariff-free Filipino sugar, and nativists who didn’t want immigration from “alien races.”

A final general argument is, perhaps surprisingly, political legitimacy. The nations that America was closest to annexing are not only economic underperformers, they also tend to be undemocratic and authoritarian. Recently, Panama and the Dominican Republic are probably exceptions here with relatively successful and stable governance.

Haiti and Cuba are extreme examples of failure. If these nations were US states or territories, they would have a far more legitimate local democracy, stable rule of law, and protections from the Bill of Rights. The process by which the US attains control of these nations would not be especially legitimate or peaceful, as is clear from the history of US control in the Caribbean. But the history of these nations after US exit hasn’t been one of peaceful political legitimacy either. Only an extreme blood-and-soil nationalist would prefer indigenous anarchy or tyranny to imperial democracy, prosperity, and rule of law.

So far, I’ve been focusing on general positive features of being integrated into the United States. These features are clear in the places that were integrated, and absent in those that were not, but the choice of integrating some and not others was not random. We probably kept the territories that were easiest to keep and let go the ones that would be too costly to retain. So beyond the general advantages of the US federal umbrella, were any of the territories we gave up actually feasible to keep without suffering massive costs?

The Philippines

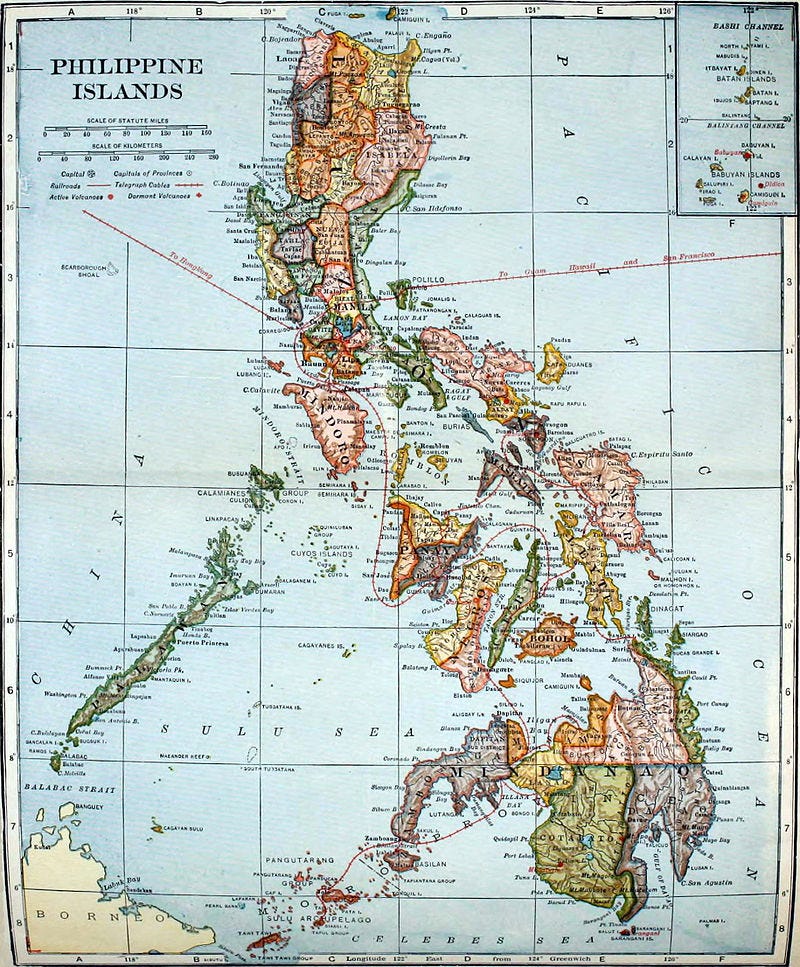

The US annexed the Philippines from Spain after winning the Spanish-American war in 1898. Fighting with Filipino nationalists began in 1899 and took the lives of 4,200 American and more than 20,000 Filipino combatants. The 1902 Organic Act transitioned out of martial rule and into an organized territorial government modeled on the American federal structure. This government was mostly controlled by presidentially appointed members to an executive branch and the upper house of the legislature, but there was a popularly elected lower house which did have some influence. Thus began the first democracy on the Philippine islands.

Over the next couple of decades, the Philippines was operated as an “Insular Government” similar to Puerto Rico before they created their current constitution in 1950. This government was, on the whole, successful, stable, and relatively just. The Spanish Catholic Church was separated from the state and its property was bought by the US. The insular government set up a property title system that allowed resident peasant holders to claim their land. Trade volumes increased 10x relative to the pre-war period and per capita GDP doubled. Slavery and piracy were suppressed, and all-cause mortality fell.

In 1916, a new constitution for the Philippines was passed under the Jones Law, which explicitly planned independence as the goal for the territory and set out the conditions under which it would be granted. Governance continued mostly as before, but the civil service was transitioned away from American staffing and by the end of 1921, around 95% of the civil service was staffed by Filipinos. In 1934 independence was officially scheduled for the Philippines in ten years. This was interrupted by the Japanese occupation of the Philippines and the re-conquest of the islands by American troops. In October of 1945 the Philippines joined the United Nations and on July 4th of the next year, their independence was officially recognized by the US.

So would it have been possible for the US to retain control of the Philippines? In a sense, the Philippines is the most likely candidate because its the only nation on this list to be officially annexed by the US. In another sense, its among the least likely because of its distance from the mainland, large size relative to the US, domestic political opponents, and how long independence had been an explicit plan for the territory.

Overall, I do think that permanent unincorporated territory status, like what Puerto Rico has, was possible without additional violence and that this would have been beneficial for both Filipinos and Americans.

How would the timeline have to change for this to happen? First of all, you'd have to go back and avoid passing the 1934 Tydings–McDuffie Act that scheduled full independence. This should be possible because earlier versions of the act were vetoed by President Hoover and voted down by the Philippine Senate, so it wasn’t hard to find opponents of the law. Filipino nationalists would be disappointed by this result, but by this point they had been peacefully sending rebuffed independence missions for 20 years, so I don't think this setback would drive them to violence. Then, it should be possible to stall on future independence missions until WW2 begins.

The end of WW2 is an important crux for this alternate history. On the one hand, much of the Philippines was completely destroyed by the war and the Philippine government was pushed into operating in exile out of Washington D.C. The American reconquest, rebuilding, and reinstallation of government in the Philippines is an opportunity to sympathetically strengthen the status of the Philippines as an American territory. On the other hand, resistance to Japanese occupation had forged a communist-nationalist guerilla movement with over 10,000 experienced fighters. In actual fact, the American and Filipino governments collaborated to defeat this rebel group, but any strategic misstep in the integration process could risk inflaming this group into a rebellion that the US could not defeat.

If the US successfully navigated this crux, the Philippines would enter into the post-war path towards closer integration with the US, along with Puerto Rico and Hawaii. Under US control before WW2, Philippine GDP per capita reached 30% of US levels but fell to around 10% after independence. If they remained as a US territory, Filipino GDP per capita would probably be 7-10 times higher than it is today, roughly matching Puerto Rico. Filipino immigrants in the US today have a median household income 25% higher than native American households and even higher than other Asian immigrant groups. Part of this success is due to selection effects that would weaken as immigration expands, but if the Philippines remained a US territory, America would have a much larger and still successful Filipino immigrant group.

This outcome is a big improvement on our current world! A hundred million people are 10x wealthier and Americans get better off as well. This outcome was probably attainable without significant extra violence, and arguably would have been less violent than our current world given the Philippines’ history with authoritarianism. We severed ties with the Philippines mostly because of nativism, nationalism, and the lobbying of interest groups who benefitted from restricted trade and immigration. Abdicating the administration of the Philippine islands and cutting them off from our labor markets, investment, and institutions was a mistake and a moral failure.

Cuba

The United States’ presence in Cuba also begins with the Spanish–American war, but unlike the Philippines, Cuba was never annexed. Congress attached the Teller Amendment to the war resolution, which “asserts its determination … to leave the government and control of the Island to its people.”

Instead of annexation, the post-war Platt Amendment essentially established Cuba as a protectorate state. The US retained broad authority to intervene in Cuban governance when its interests or the interests of American property owners on the island were threatened. Over the next few decades, the US would use this authority several times to control protest and rebellion after contested elections and protect American sugar cane plantations. In 1934, Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor Policy” tried to distance Cuban internal politics from American intervention, but still held on to naval basing rights in Guantanamo.

The Cuban republic that followed never stabilized. Fulgencio Batista’s 1952 coup undermined constitutional rule, and the 1959 revolution brought nationalization, dictatorship, and stagnation.

Like the Philippines, the reluctance to integrate Cuba was based mostly on selfish nativism and fear of competition from Cuban sugar farmers, rather than any benevolent belief in national self-determination. Cuba’s geographic proximity to the mainland, closer cultural and economic ties, and smaller size relative to the US increase its feasibility as a permanent territory or state, like Puerto Rico or Hawaii. However, the actual timeline of Cuban-American relations doesn’t give us as much evidence for how costly permanent integration would be, since the Teller Amendment guarantee of independence is always there to reassure potential nationalist rebels.

So how would the timeline need to change for Cuba to be part of the US today, and how costly would these changes be? You’d probably have to start by convincing American sugar beet farmers to drop their lobbying in support of the Teller Amendment. It’s hard to tell how dropping this independence guarantee would change the actions of Cuban nationalists, and in particular whether a costly guerilla war against American control would ensue after peace with the Spanish.

It’s worth noting that the scale of resistance to America’s several military interventions in our current timeline was small. Cubans generally celebrated America’s war against the Spanish, who were far crueler masters. When the US essentially re-established martial law in Cuba from 1906-1909 after a rebellion against a contested election, there was essentially zero violent resistance, and a similar story with the Sugar Intervention in 1917. All of these interventions were backed by the path to independence in the Teller Amendment but still, the mild response suggests that the Cuban people were not intractably hostile to American government.

Higher costs of integration are difficult to rule out in Cuba’s case, but large benefits from American annexation are nearly certain. Cuba’s dismal political and economic outcomes set a low bar for counterfactual welfare that American integration can easily exceed, even if annexation creates more conflict in the early 20th century. All the benefits discussed in the Philippine case apply equally or more so to Cuban integration. An insular territorial government like the one set up in Puerto Rico or the Philippines would be far more stable, democratic, and prosperous than Cuba’s actual oscillation between right-wing coup d'état and leftist revolution.

Panama

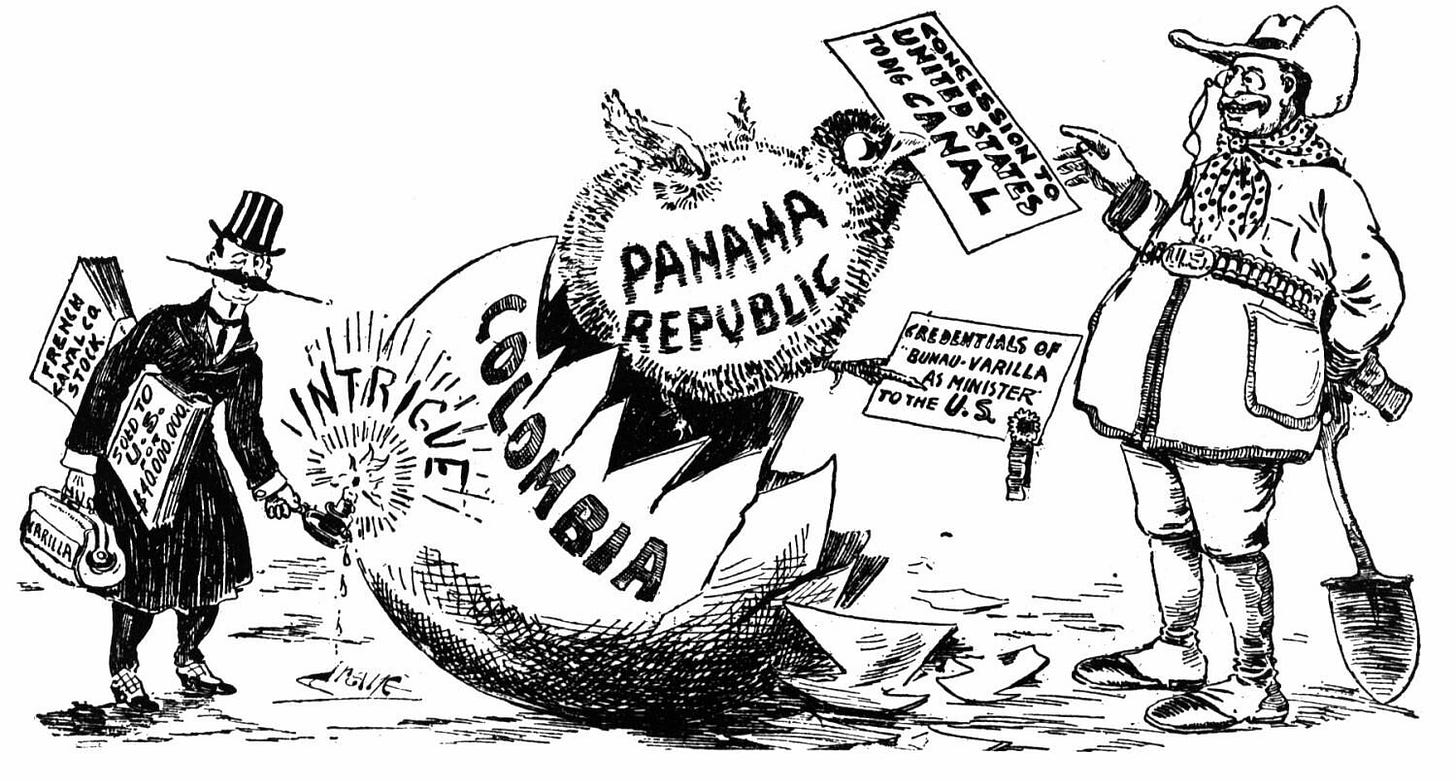

Panama was created as an American imperial project. After negotiations for canal rights with the Colombian government fell through in 1903, American investors and the military intervened to support the Panamanian independence movement and quickly recognized its sovereignty, on the condition that America be granted exclusive control of a 10-mile strip that bisected the country along the canal route.

This legal structure makes integration of Panama extremely costly from the beginning, since the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty explicitly trades canal rights for protection of Panama’s sovereignty. The geographic structure of the canal zone makes retention of that land as exclusive American territory costly as well; the cost-benefit ratio of keeping territory roughly scales with the perimeter-to-area ratio. Panama also performs the best out of all the former American protectorate states or territories in terms of per capita GDP and political stability/legitimacy (though still not without struggles).

All the arguments about the benefits of free trade, immigration, and American institutions from above still apply here, but the bigger costs of annexation and the lower benefits compared to Panama’s best-in-class performance probably make the alternate history of greater US control in the area no better than the actual outcome on net. Perhaps if the US had outright annexed the territory from Colombia from the beginning, it could have stably retained the territory and Panama would be much more stable and wealthy today. But after structuring the Canal deal as a concession from a guaranteed independent nation, it probably wasn’t optimal to get back on the path towards an American Panama.

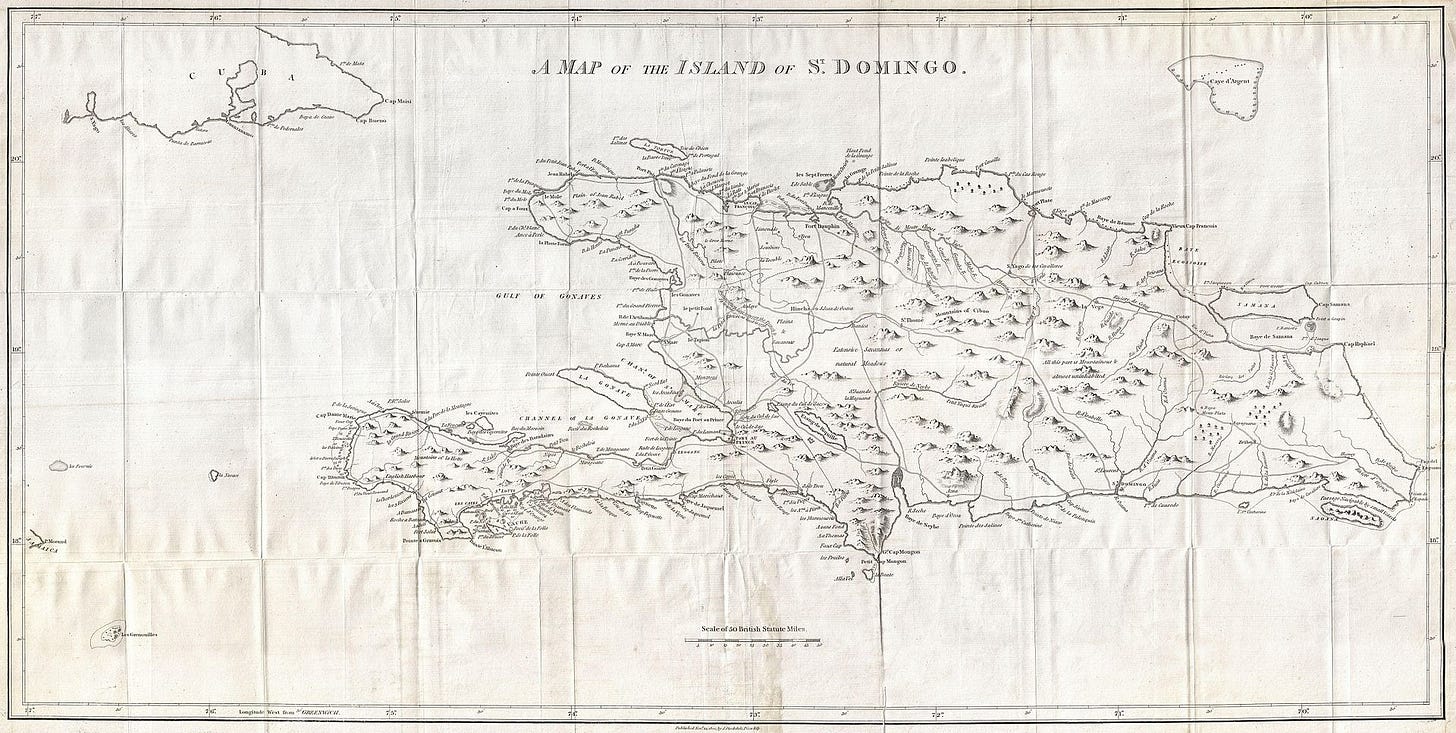

Hispaniola

The island of Hispaniola, the current home of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, broke from its colonial overlords earlier than the other nations on this list. Haiti first broke from the French in 1804, while the territory that would become the Dominican Republic remained unhappily under Spanish rule until 1822. In that year, the President of Haiti led 10,000 troops across the border, unifying the island and ousting the Spanish. Eventually, the Haitian leadership became unpopular on the eastern side of the island and after a prolonged resistance movement and civil war, the Haitians were themselves ousted and Dominican Republic was born.

Thus began several decades of perpetual conflict between the left and right halves of the island, with the Dominican Republic generally the weaker half at risk of annexation. So much so that they even briefly accepted re-annexation by the Spanish in the early 1860s, only to rebel again a few years later.

It is in this context that the President of the Dominican Republic negotiated a treaty with President Grant of the United States in 1870 whereby the embattled eastern half of Hispaniola would be annexed by the US. This annexation plan was supported by the executives of both nations, by prominent abolitionists like Frederick Douglas, and probably by most of the Dominican people, who feared invasion more than anything else, although the suspiciously high 15,169 to 11 vote in favor of annexation was influenced by state intimidation. Unfortunately, President Grant and the annexation treaty had enough opponents in the Senate for the treaty to lose in a 28-28 vote.

So for the Dominican Republic, the alternate history is easy. Simply approve their request for annexation in 1870 and the DR would be a secure part of the United States today, with all of the wealth and freedom afforded by membership in the American republic. The US had later chances to annex the DR, and we did establish establish a military government and a financial protectorate there in the 1920s, but accepting this earlier annexation is the better path.

Haiti’s path was uglier. After President Vilbrun Guillaume Sam’s lynching in 1915, U.S. Marines occupied the country until 1934 and ran a martial government. The Caco War was a prolonged insurgency that cost thousands of lives. The use of the Corvée forced labor system caused abuse and rebellion. A 1921 Senate inquiry documented excesses and civilian deaths in the thousands.

None of these costs are small or easy to ignore. But here it’s important to remember that the net effect of American annexation of Haiti should be compared to the actual outcomes of independence that we observe today. This baseline is catastrophic. As it is today, Haiti has decades of extreme poverty, chaos, and violence both in its past and its future. If Haiti had become a US state or territory earlier in the 20th century, they would be on a path to stability and wealth like Puerto Rico.

The American leaders of 1918 inherited a choice that we no longer have. The costly and morally suspect conquests of their ancestors has given them leverage over institutions that hundreds of millions of people now depend on for their prosperity, freedom, and security. They could either consolidate that inheritance, imperfect though it was, into a durable framework of free trade, immigration, and shared rule of law, or they could walk away.

Narrow considerations of nativism and economic special interests dressed in the rhetoric of anti-imperialism and national self-determination pushed them to abrogate this choice and walk away, at the expense of future welfare. The places America kept: Hawaii, Alaska, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, achieved stability, democracy, and high living standards. The places it abandoned: Cuba, Haiti, and the Philippines, fell into cycles of dictatorship, stagnation, and collapse. By renouncing empire, America absolved itself of colonial responsibility, but it also abandoned hundreds of millions to worse outcomes than they likely would have had under American rule.

Empire corrupts the republic, as it did in Rome. If the choice is between Empire and Republic, choose the latter, for what profit to conquer the world, when you have lost your soul.

If we had annexed Cuba and Hispaniola, it wouldn't feel like an "empire". They are much closer to the continental US than Alaska or Hawaii, closer than Puerto Rico is. It would just feel like, well naturally we also control some of the nearby islands.

To me I wonder whether we could do a better job of integrating Puerto Rico. Yeah, it's richer than the surrounding islands, but it's far poorer than the US states. I feel like as long as most people there don't speak English, it's going to be hard for them to get the full benefit of being US citizens. And if we really find a formula for making Puerto Rico as well off as Miami, then yeah, I will wish that in retrospect we had done the same for Cuba and Hispaniola.