The NIH Doesn't Fund Small Crappy Trials

Simpson's paradox in the wild

One of the most important things the NIH does is fund clinical trials. The life expectancy gains from progress in medicine are at least as valuable as all consumption gains over the 20th century, and the NIH’s contribution to this progress is significant. They fund several hundred trials a year directly and indirectly support many thousands more with early results and basic research.

Because of this importance, the NIH’s clinical trial enterprise rightly receives a lot of focus from science policy researchers and advocates. One common narrative in this group is that the NIH funds too many “small crappy trials.” That quote is from a FDA higher up, but the story has been repeated by many others.

The idea is that the NIH is particularly likely to fund low sample size trials with poor targeting that may not even be randomized. Each of these trials produces little to no scientific value while the sum of their parts — combining all the enrollment into one big trial — would be enough to answer some important medical questions. The NIH continues to fund these crappy trials because the priorities of the researchers proposing these trials are misaligned with the social value of their research. They can get a publication out of their trial whether we learn something important or not.

This narrative is compelling and does point out some real incentive problems in the NIH’s researcher guided funding model but does it hold up in the data?

I downloaded all of the clinical trial data from ClinicalTrials.gov to find out. The data here track the funder of the trial, the enrollment, the study design and several other variables. Plotting out the average enrollment in interventional trials by funder provides evidence for the narrative that NIH trials are small.

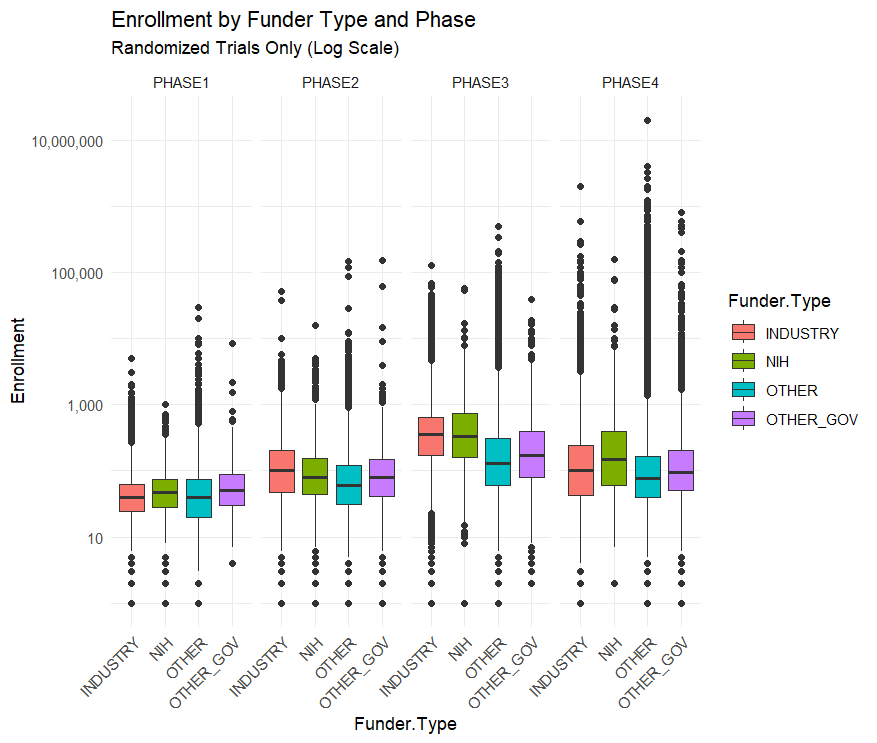

The graph above is on a log scale because there are some huge outlier trials like the Phase-4 AstraZeneca Covid-19 trial which has a listed enrollment of 18 million.

The median NIH funded trial has 48 participants while the median industry funded trial has 67. The average NIH funded trial has 288 participants while the average industry trial has 335 and the average “Other” funded trial (mostly universities and the associated hospitals) has 923 participants.

By median or by average NIH trials are the smallest out of all the funders. This seems to confirm the “small crappy trials” narrative, at least partly. You need a sample size bigger than 48 to detect anything except the largest effects so trials of this size are likely to be underpowered or, in other words, crappy.

This narrative is reversed, however, when you split up the trials by phase.

Across all trials NIH funded ones are the smallest, but within each phase NIH trials are the largest or second largest. Their overall small enrollment average is just due to the fact that they fund more Phase I trials than Phase III. But NIH Phase I trials have a bigger sample size than industry funded trials on average.

This is an example of Simpson’s Paradox in the wild!

Arguing that the NIH should stop funding unusually small trials is easy but arguing that they should shift from funding the Phase I trials closest to basic research towards later stage trials is less clear.

The NIH’s clinical trial strategy is certainly not perfect and improving it is valuable. But a systematic bias towards “small crappy trials” doesn’t really seem like it’s an important problem facing the NIH.

Do you think the NIH should use more innovative prizes or is that not an appropriate tool for the agency?

Thanks for the interesting analysis, but I don't understand the logic here.

Claim: The NIH funds a lot of small, crappy trials

Data: The (Phase I) trial size is similar for NIH and for other funders

How does the data counter the claim? Couldn't one simply conclude that *every funder* funds too many small, crappy trials?

(I posted this comment on MR, as well.)