The Timeless Way of Building

Christopher Alexander on the design of cities and homes

Almost everyone is at peace with nature: listening to the ocean waves against the shore, by a still lake, in a field of grass, on a windblown heath. One day, when we have learned the timeless way again, we shall feel the same about our towns and we shall feel as much at peace in them, as we do today walking by the ocean, or stretched out in the long grass of a meadow.

- Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building

Christopher Alexander was an American design theorist and architect whose philosophy and works have been influential since their origins in the mid-to-late 20th century. Alexander’s teaching at Berkeley and his contributions to the design theory of programming have earned him an enduring place in Silicon Valley intellectual culture.

I read his books, The Timeless Way of Building and A Pattern Language, searching for answers to the ongoing debate about why buildings and cities are so ugly today.

Synopsis

The central idea of The Timeless Way is that the design of buildings and cities isn’t reducible to the pure visual art of carving geometric forms out of volumes, but neither is it infinitely complex and contextual. Rather, it is the art of fitting together patterns, like Legos. Tastefully pick 20 patterns from a set of 200 or so and you’ll make a building that is beautiful.

The patterns that define a building, or a city, or a life, arise from the events which keep on happening there most often. For example, the pattern of events that govern Alexander’s life:

Being in bed, having a shower, having breakfast in the kitchen, sitting in my study writing, walking in the garden, cooking and eating our common lunch at my office with my friends, going to the movies, taking my family to eat at a restaurant, having a drink at a friend’s house, driving on the freeway, going to bed again. There are a few more.

There are surprisingly few of these patterns of events in any one person’s life, perhaps no more than a dozen. Not that I want more of them. But when I see how very few of them there are, I begin to understand what huge effect these few patterns have on my life, on my capacity to live. If these few patterns are good for me, I can live well. If they are bad for me, I can’t.

Or the pattern of events in Lima, Los Angeles, and a medieval town:

What is Lima—what is most memorable there—eating anticuchos in the street; small pieces of beef heart, on sticks, cooked over open coals, with hot sauce on them; the dark, badly lit streets of Lima, small carts with the flickering fire of the hot coals, the faces of the sellers, shadowy figures gathered round, to eat the beef hearts.

When you think of Los Angeles, you think of freeways, drive-ins, suburbs, airports, gas stations, shopping centers, swimming pools, hamburger joints, parking lots, beaches, billboards, supermarkets, free-standing one-family houses, front yards, traffic lights . . .

When you think of a medieval European town, you think of the church, the marketplace, the town square, the wall around the town, the town gates, narrow winding streets and lanes, rows of attached houses, each one containing an extended family, rooftops, alleys, blacksmiths, alehouses . . .

The list of elements which are typical in a given town tells us the way of life of the people there.

And, what is most remarkable of all, the number of the patterns out of which a building or a town is made is rather small.

One might imagine that a building has a thousand different patterns in it; or that a town has tens of thousands . . .

But the fact is that a building is defined, in its essentials, by a few dozen patterns, and, a vast town like London, or Paris, is defined, in its essence, by a few hundred patterns at the most.

Buildings and towns are defined by the patterns which repeat themselves there, but some buildings and some towns are full of life, and others less. The right patterns can make a place live or die.

Consider an example on the smallest possible scale: A prayer rug

The old Turkish prayer rugs, made two hundred years ago, have the most wonderful colors.

All of the good ones follow this rule: wherever there are two areas of color, side by side, there is a hairline of a different third color, between them. This rule is so simple to state. And yet the rugs which follow this rule have a brilliance, a dance of color. And the ones which do not follow it are somehow flat.

Ornamental decorations on a building work in much the same way:

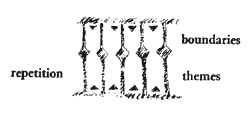

Search around the building, and find those edges and transitions which need emphasis or extra binding energy. Corners, places where materials meet, door frames, windows, main entrances, the place where one wall meets another, the garden gate, a fence - all these are natural places which call out for ornament.

Now find simple themes and apply the elements of the theme over and again to the edges and boundaries which you decide to mark. Make the ornaments work as seams along the boundaries and edges so that they knit the two sides together and make them one.

Or an independent discovery of similar patterns in Islamic geometric art by a Slate Star Codex reader who is, as far as I know, unaware of Alexander’s work.

To pare it down to the essentials, the first few rules [of Islamic geometric art] all serve to maintain the impression that the designs are formed by interweaving lines that either extend infinitely or connect into loops.

First, lines should never terminate except at the boundary of the entire design.

Second, lines must maintain their direction before and after crossing another line.

Third, within a single design, lines should only turn or intersect at a limited set of compatible angles.

Similar rules exist for building beautiful rooms.

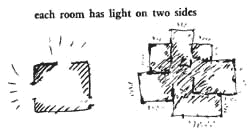

The light in many glorious rooms is also governed by a simple rule.

Consider the simple rule that every room must have daylight on at least two sides (unless the room is less than 8 feet deep). This has the same character, really, as the rule about the [Turkish rug]. Rooms which follow this rule are pleasant to be in; rooms which do not follow it, with a few exceptions, are unpleasant to be in.

And for buildings:

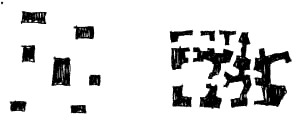

Outdoor spaces which are merely “left over” between buildings will, in general, not be used.

There are two fundamentally different kinds of outdoor space: negative space and positive space. Outdoor space is negative when it is shapeless, the residue left behind when buildings—which are generally viewed as positive—are placed on the land. An outdoor space is positive when it has a distinct and definite shape, as definite as the shape of a room, and when its shape is as important as the shapes of the buildings which surround it.

And for towns:

The artificial separation of houses and work creates intolerable rifts in people’s inner lives.

In modern times almost all cities create zones for “work” and other zones for “living” and in most cases enforce the separation by law.

But this separation creates enormous rifts in people’s emotional lives. Children grow up in areas where there are no men, except on weekends; women are trapped in an atmosphere where they are expected to be pretty, unintelligent housekeepers; men are forced to accept a schism in which they spend the greater part of their waking lives “at work, and away from their families” and then the other part of their lives “with their families, away from work.”

Throughout, this separation reinforces the idea that work is a toil, while only family life is “living” - a schizophrenic view which creates tremendous problems for all the members of a family.

What are the requirements for a distribution of work that can overcome these problems?

1. Every home is within 20-30 minutes of many hundreds of workplaces.

2. Many workplaces are within walking distance of children and families.

3. Workers can go home casually for lunch, run errands, work half-time, and spend half the day at home.

4. Some workplaces are in homes; there are many opportunities for people to work from their homes or to take work home.

To make a beautiful Turkish rug or Islamic geometric design, there are three or five essential rules to follow. How many do you need to make a beautiful room, building, or town?

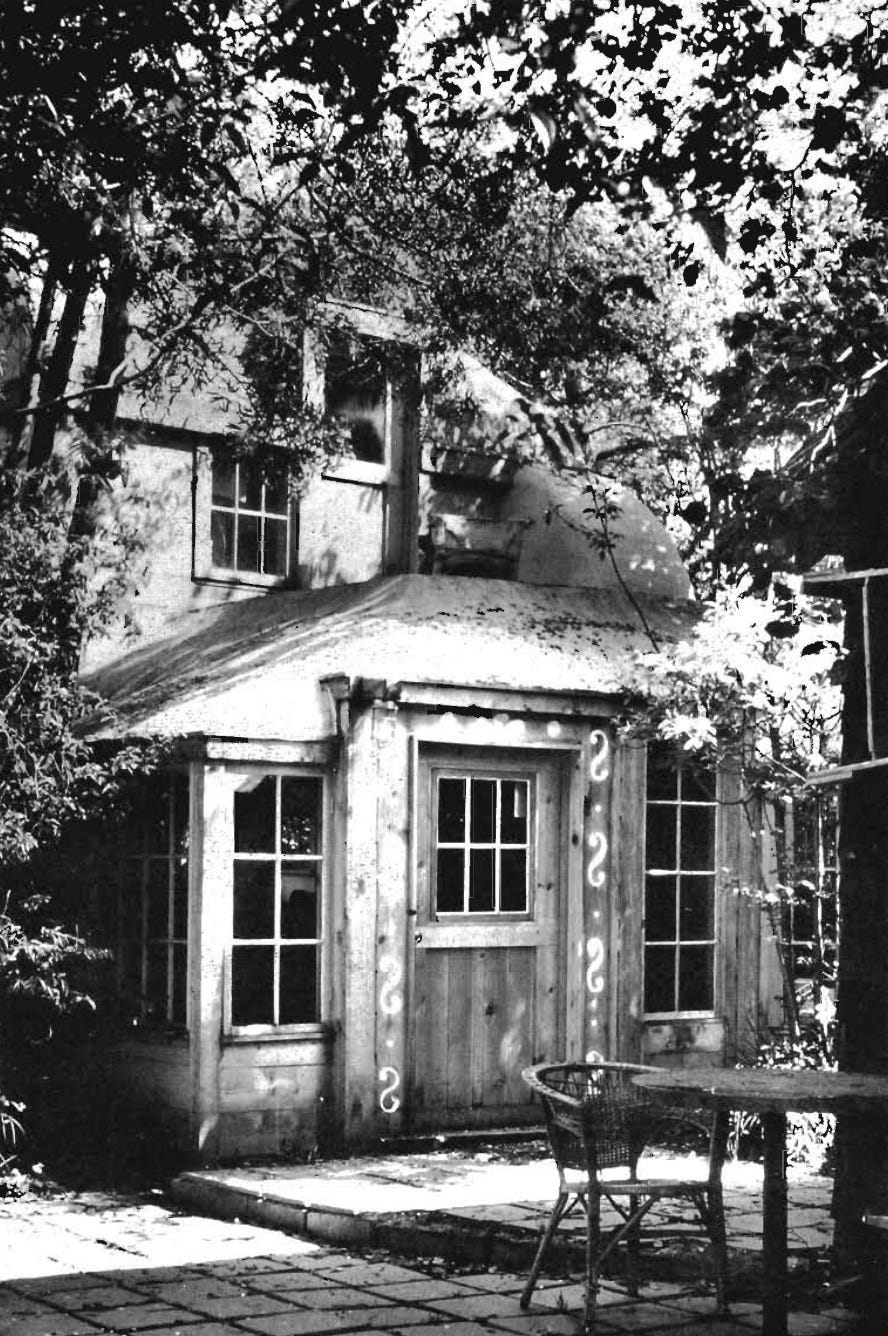

It’s not just one rule, like “form follows function.” But neither is it so complex and contextual that writing down rules to follow is impossible. It takes a couple dozen patterns to build a beautiful building. Here are the patterns Alexander used to build a small cottage,.workshop, and guest house in the back yard of the house he used as his office, starting from the broadest patterns and going to the most specific.

Work Community, The Family, Building Complex, Circulation Realms, Number of Stories, House for One Person, South Facing Outdoors, Wings of Light, Connected Buildings, Positive Outdoor Space, Site Repair, Main Entrance, Entrance Transition, Cascade of Roofs, Roof Garden, Sheltering Roof, Arcade, Intimacy Gradient, Entrance Room, Staircase as a Stage, Zen View, Tapestry of Light and Dark, Farmhouse Kitchen, Bathing Room, Home Workshop, Light on Two Sides of Every Room, Building Edge, Sunny Place, Outdoor Room, Connection to the Earth, Tree Places, Alcoves, Window Place, The Fire, Bed Alcove, Thick Walls, Open Shelves, Ceiling Height Variety

Why are Buildings Uglier Today?

Alexander’s philosophy of how to design beautiful places is compelling and exciting. But his theories add conflict to the central question of why buildings and cities have become uglier over time because they place the blame for the decline of beauty squarely on what makes cities valuable in the first place: Scale.

Reading The Timeless Way only reinforces the impression that the pre-modern towns of Europe, Asia, and parts of the American East Coast, reflect so much more life, more humanity, and more of that “quality without a name” than their post-modern counterparts. But the question is why?

The major enemy is scale.

For example, Alexander claims that the breakdown of design is caused by a growing alienation between the people who use a building and the people who design it.

In agricultural societies, everyone knows how to build; everyone builds for himself, and helps his neighbor build…

But, by contrast, in the early phases of industrial society which we have experienced recently, the pattern languages which determine how a town gets made become specialized and private. Roads are built by highway engineers; buildings by architects; parks by planners; … tract housing by developers …

Those few patterns which do remain within our languages become degenerate and stupid.

The users, whose direct experience once formed the languages, no longer have enough contact to influence them. This is almost bound to happen, as soon as the task of building passes out of the hands of the people who are most directly concerned, and into the hands of people who are not doing it for themselves but for others.

He thinks the scales of modern cities are now too large for effective local government:

Individuals have no effective voice in any community of more than 5,000-10,000 persons … Therefore: decentralize city governments in a way that gives local control to communities of 5,000 to 10,000 persons. Give each community the power to initiate, decide, and execute the affairs that concern it closely: land use, housing, maintenance, streets, parks, police, schooling, welfare, neighborhood services.

That cities are too large to provide everyone access to the amenities of the downtown:

There are few people who do not enjoy the magic of a great city. But urban sprawl taks it away from everyone except the few who are lucky enough, or rich enough, to live close to the largest centers … Therefore, put the magic of the city within reach of everyone in a metropolitan area. Do his by means of collective regional policies which restrict the growth of downtown areas so strongly that no one downtown can grow to serve more than 300,000 people.

And that buildings themselves are too large:

There is abundant evidence to show that high buildings make people crazy. High buildings have no genuine advantages, except in speculative gains for land owners … Therefore, in any urban area, no matter how dense, keep the majority of buildings four stories high or less. It is possible that certain buildings should exceed this limit, but they should never be buildings for human habitation.

The ever-growing layers of hierarchy that enable a world of world-cities also create principal-agent problems between designers and users, voiceless political constituents, and demand for hulking transport infrastructure.

Alexander’s ideal town arises from a process of decentralized, small scale “repair.”

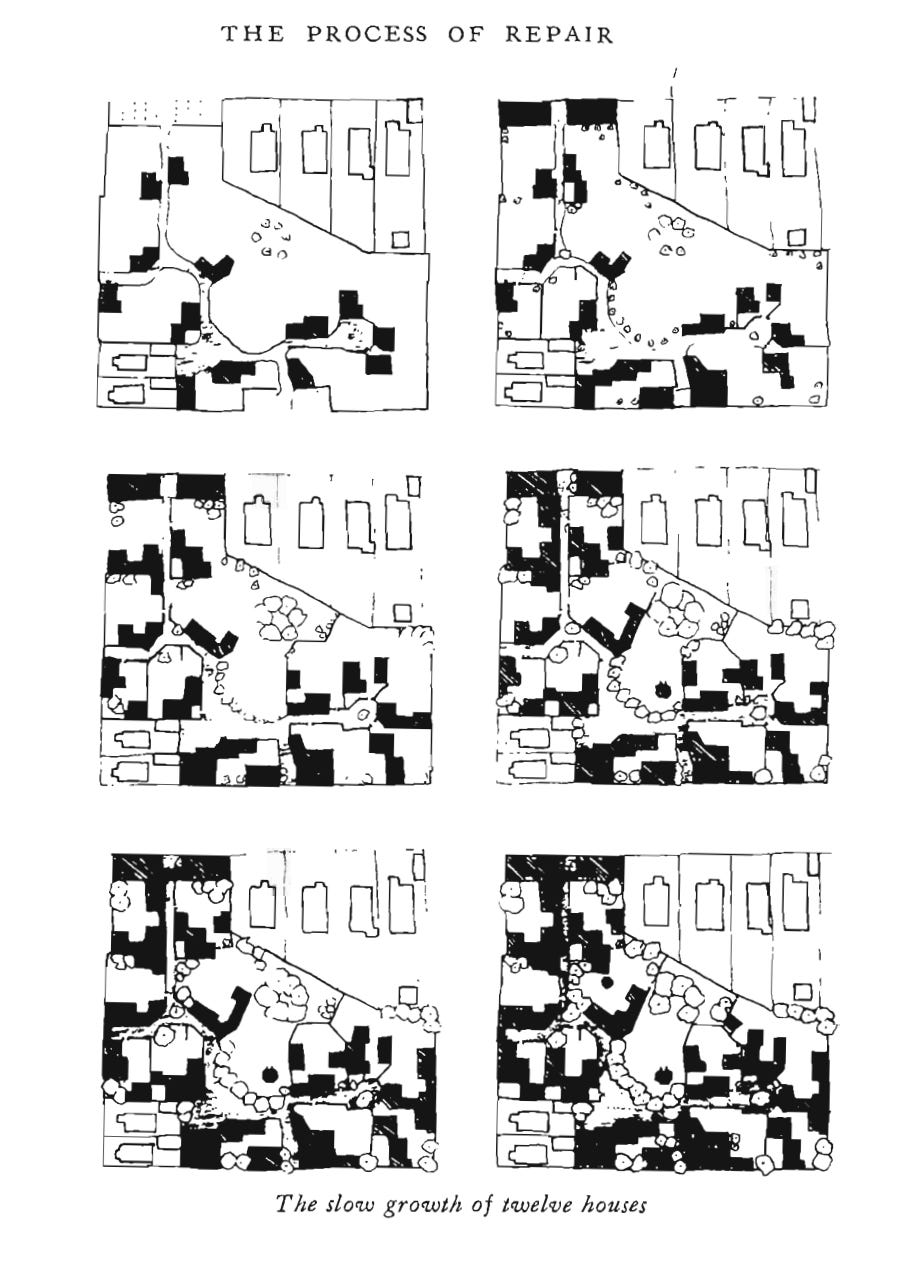

Let us imagine a cluster of houses growing over time.

Each house starts with a small beginning—no more than a family kitchen, with a bed alcove off one end, and a kitchen counter.

All in all, no more than 300-500 square feet to start with.

Then, for the first few years, people add 100-200 square feet more each year.

First a bedroom perhaps; another bedroom; a workshop; a garden terrace; a full bathing room; arcades and porches; studio; a bigger sitting room, with a big fireplace; a garden shed. And, at the same time common things are also built; they plant an avenue of trees; a small gazebo; a shared outdoor room; paving on the paths . . .

As the buildings reach maturity, the increments get smaller. Yet, at the same time, collectively, the houses begin to generate the large patterns which define the cluster.

Each person begins to work with his neighbor, first the neighbor on one side, then the neighbor on the other side; and together they try to make the space between their houses beautiful.

So, the houses get their form, both as a group, and separately, as individuals, from the gradual accretion of a number of small separate acts.

Alexander is correct to notice that scale has changed almost everything about our relationship to the built environment compared to pre-modern cities. And he insightfully describes the decentralized, incremental process of construction that led to some of the most beautiful towns ever made. In this way, he provides a compelling answer to the question that motivated this post. Our buildings and towns are worse today because of scale.

But his offered solutions require impossible sacrifice and political coordination. If the only way to improve the built environment is to have every person build their own house, to restrict the size of local governments to 7,000, and to keep the size of cities below 300,000, then our built environment will not improve.

Alexander’s prescriptions against scale also conflict with economist’s view on the value of cities in the first place. Cities are labor markets and the bigger they are, the more efficient they get. In larger cities there is more specialization in production, more shared infrastructure, there are more knowledge spillovers, more competition, and better matching between workers and firms.

I am predisposed to be suspicious of Alexander’s top-down designs, and many of them are ridiculous. The transition between agricultural and urban land, building heights, and the location of CBDs are not appropriately decided by central authorities.

However, I found it difficult to sustain my suspicion against all of Alexander’s ideas. I wanted to dismiss all of the designs for things beyond an individual’s control as something that should be left to the decentralized order of the market. But for so many things this is an empty position that ignores the possibility of mistakes among market participants, who are influenced not only by market forces, but also by cultural ideas about building.

The lifeless Lennar homes suburbs that tile the sunbelt are in a sense outcomes of decentralized order. But they are nonetheless designed by individuals who could make better decisions and improve the world.

The team behind California Forever is operating in a market, but they have to make decisions about where to place the roads, the public services, how many trees to put in, how to integrate water features, even where to locate certain types of land use. If they follow certain patterns of building, their city will be dead. If they follow others, it can be electric with life.

Perhaps over some sufficiently long term, the cities and subdivisions that build well reward their owners more than the ones they don’t, thus pushing towards good design with an invisible hand. But cities are durable, both physically and economically as the increasing returns make it difficult to compete with cities that are already large. European cities are still stuck with Roman decisions about city locations and design, The mistakes of urban renewal still scar our cities 50 years later. Mistakes in city building are too durable to rely only on the slow, decentralized punishments of the market.

Even Alain Bertaud in Order Without Design says that while most things in a city should be left to the market, roads and public services have to be designed top-down. Bertaud’s book is arguing against city master plans even more wildly prescriptive than Alexander in his book, but from my perspective this admission gives up the whole game! After placing the roads and public spaces a city’s entire skeleton is defined. This skeleton more than anything else makes up the difference between Amsterdam, New York, and Phoenix.

The Timeless Way and A Pattern Language are best when they are insightfully describing the natural interactions between humans and built form. And when explaining why these interactions have gotten worse since around the invention of the automobile. But unfortunately, Alexander’s books are at their weakest when they are prescribing solutions to this problem. By only offering solutions that require sacrificing so much that is good about the modern world, they end up with no real solutions at all.

The more difficult and more useful challenge is finding a way to improve our buildings and cities that is consistent with the economies of scale that our modern world will never give up.

Pattern languages, the residue of repeated human interaction with design, are real. A prayer rug needs three colors at every edge. A room needs light from two sides. A dozen rules make the difference between a dead place and a living one. If the developers building California Forever, the architects designing 5-over-1 apartment complexes, or the planners laying out the next sunbelt suburban subdivision studied these patterns and applied them, they could make their building beautiful.

But Alexander gives us no advice on how to get these parties to design more thoughtfully. Thus, we are left with a vocabulary for what makes places alive, but no means of making it matter to the people who actually build our world.

Great post. You make a great point around how Alexander's work is good at pointing out the problems & the patterns but less on how to apply these insights to a world that depends on large-scale development and economies of scale.

My take is that Alexander's personal dislike of scale was actually a bias that made his theories and prescriptions less helpful (especially when they moved into more macro aspects like his city/town prescriptions in earlier books).

One thing I wanted to share is that Alexander's theories developed more after writing "A Pattern Language"; his final set of books is called "Nature of Order" and I think it evolved his thinking a bit. I wrote about the books a few years back in a series of posts in case that's of interest. It can be a bit abstract but I love to think about his work :) https://mysticalsilicon.substack.com/p/how-to-make-living-systems

Thanks for writing :)

Thanks for this Maxwell, I've stored this for closer reading. The strange disappearance of beauty as a consideration is extremely beguiling and important. I've written a little on it here - https://clubtroppo.com.au/2008/09/27/architecture-and-beauty-some-thoughts/ and here https://clubtroppo.com.au/2008/02/16/liveability/

And even made some videos on it would you believe.

https://youtu.be/BxNdnpGbfFg?si=vADW-HZRNiqsfeut

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/zYHdQipaGOs