Most Externalities are Solved with Technology, Not Coordination

Econ 101 Needs More Progress Studies

The basic externalities story goes like this: Some things, like air quality or scientific discoveries, have effects which spread to millions of people without cost or reward to the creator. Actions with unpunished costs are over-produced and actions with uncompensated benefits are left undone.

The story continues that if only we could coordinate, we could fix the misallocation caused by externalities. We might get the government to tax and subsidize externalities or else we might try to lower transaction costs so that people can bargain to solve externalities on their own.

The basic story over-focuses on social coordination as the solution to externalities. Our institutions cannot be relied on to optimally correct externalities or even to avoid making them worse. Usually, the costs of an externality subside only after we’ve invented a technology which makes it cheap or privately beneficial to do the socially optimal thing. Most importantly, technology shifts out the production possibilities frontier making it possible to get outcomes beyond what even perfect social coordination could attain.

Economics should emphasize the importance of technology as a solution to externality problems and focus less on social coordination.

The Smoky City

Consider Pittsburgh in the mid-20th century. Coal and steel industry earned the city the nickname “smoky city” and caused widespread death and disease. Coal was used for everything in Pittsburgh: steel and industry, heat and light. Buildings and people were stained black inside and out.

Coal pollution is a classic externality problem and indeed the classic solutions were tried. There were political and social campaigns for cleaner air in the city throughout the early 20th century. These culminated in a 1941 law that put some requirements on residential users to use treated coal, other cleaner fuels, or special burners that reduced smoke.

But ultimately, the solution to this externality problem came from technology. First, coal-gas burner-lamps were replaced with electric ones. Then, Pittsburgh got a natural gas and petroleum pipeline laid nearby. Revenues from utility sale of natural gas doubled from $67 million in 1938 to $140 million ten years later. The growth of natural gas replaced coal in heat and power generation for Pittsburgh and made more total energy available for its residents. Similarly, coal trains were replaced by diesel trains. In 1955 the Bureau of Smoke Prevention observed that “The Diesel locomotive has solved the smoke problem of the railroads.”

Social and political coordination did play some role in this story. The 1941 smoke control ordinance coincided with some of these changes and may have made some contribution to the shift. However, enforcement the law was delayed until 1947 to aid in wartime production and the coal-union economy of the city led to concessions being made against the law for industrial uses (a different form of political coordination).

National energy consumption from coal peaked, except for a brief post-war spike, in the 1920s, long before air quality legislation was passed. Hours of heavy smoke per year in Pittsburgh were declining long before the 1941 ordinance. Joel Tarr and Karen Clay of Carnegie-Mellon university agree that “A transition to natural gas, rather than public policy, produced the city’s first clean air period.”

More important than the fact that a technological innovation solved Pittsburgh’s smog where political coordination failed is the following point: Even if the social coordination had worked perfectly the technological solution would still be more important. The socially optimal tradeoff between coal energy and clean air available to Pittsburgh in 1905 still leaves them in a bad situation. They had to accept either dirty air or energy poverty; they had no way to solve both problems at once. The technological solution pushes the production possibilities frontier between energy and air quality far beyond what was the optimal point when only coal was available.

Airborne Disease

Infectious diseases have been humanity’s deadliest foe for essentially all of its urban history, not least because they create costly externalities. Diseases spread exponentially, so a single infection can lead to thousands of others down the line without making patient-zero any more sick.

Dozens of social and political coordination strategies have been designed to address this externality from the original 40-day quarantines for ships entering medieval Venice to covid mask-mandates and school closures. These have had various degrees of success across thousands of years of attempts but they often fall short of appropriate protection or overshoot the optimum and suffer needless costs.

No coordination strategy ever got close to the effectiveness of vaccines. Vaccines have saved billions of lives in their relatively short history and have completely eradicated many diseases with a finality that no coordination could ever achieve alone.

Vaccines of course create their own coordination problems, but inventing the technology is the essential step that allows humans to live in big groups without constant death. The socially optimal response to disease without vaccines was rarely, if ever, reached. Even if you did get perfect coordination, that either means tiny, dispersed cities with infrequent contact or else frequent deadly disease. Only vaccines allow us to avoid both at the same time.

Firefighting

Large scale city fires like the fire of London or Chicago were serious threats before the 20th century. Just like with disease, there is a clear externality problem. One building catching fire poses an external risk to entire neighborhoods. Various social coordination approaches have made progress against this externality, from public fire brigades to those run by private insurance companies to building codes that mandated setbacks and separation between structures to prevent conflagrations.

Again, our current success against this problem relies on technological improvements. Mass produced steel and concrete allow us to produce much more fire resistant buildings. Automated sprinkler systems and smoke detectors shut down fires fast when they do arise. There are fewer than half as many home fires in the US today as in 1980. Our firefighters are barely ever called to actual fires. Often, laws enforce the use of fire resistant technologies but their widespread use is still mostly due to the technological progress which led to their invention and which lowered their cost enough for legal enforcement to be an acceptable political compromise.

Over-farming and Guano Depletion

From the beginning of human agriculture until the 20th century, soil resource depletion has been a major problem. If you grow the same crop in the same field many seasons in a row, the surrounding soil will run out of nutrients and become unproductive. If enough farmers deplete their soil it can lead to ecological collapses like the Dust Bowl, thus creating external costs to other farmers.

One source of extra nutrients were guano deposits found in the early 19th century on Peruvian islands. In the age of colonialism, property rights to these islands were sometimes unclear and contested, so over-exploitation led to their complete depletion.

Social and political coordination mechanisms often tried and often failed to solve these problems.

In 1910, Fritz Haber invented a chemical process that could produce ammonia, an essential ingredient in fertilizer, out of nitrogen in the air. This process internalized the costs and benefits of fertilizer production and use. It meant that farmers need not rely on one another to maintain soil nutrients or on industrialists to preserve the guano producing environments that they relied on for fertilizer. Plus, it made fertilizer and food much more abundant creating and saving billions of lives!

Malthusian Externalities and The Industrial/Green Revolutions

In a Malthusian world, any gains in productivity are translated into higher populations which compete incomes back down to subsistence. The graph below shows that countries around the world with higher agricultural land productivity had higher population densities, but the same subsistence-level incomes per person.

People are thus not strongly incentivized to improve productivity since it will just turn into more mouths to feed. Maybe some of that population growth is carrying their own genetic code, but most of it is an external benefit to others.

There were many social and political coordination strategies that attempted to address this. For example, infanticide was an extremely common practice in pre-industrial societies to try to control population growth. Paul Ehrlich infamously advocated for mass sterilizations of women in the third world in an attempt to control what he saw as Malthusian-externality population growth which would lead to terrible famine.

You can decide for yourself how effective or necessary these coordination strategies were at addressing Malthusian externalities, but again the point is that technology has solved this problem more effectively and freed us from the terrible tradeoffs it imposes. First the industrial revolution in the west and later the green revolution in the third world raised the rate of resource growth enough that it could persistently outpace population growth and create rising incomes.

Counterexamples

While it’s true that technology is underrated as a solution to externality problems, it’s not a universal rule that technology always solves them and political coordination always fails.

Leaded gasoline is a good counterexample. You still needed technology to invent the catalytic converter, but this story is not one where we just invented a new type of fuel which made the socially optimal choice coincide with the privately optimal one. The emissions requirements from government were a necessary push to remove lead emissions from cars. Perhaps electric vehicles would have eventually done the same but still, political coordination saved us from decades of lead emissions.

Another important point is that technology itself is a big externality problem! Inventors collect only a small portion of the value they create with their ideas. The private sector still outspends the government on R&D by 4:1 and the design of government subsidies can often make them counter-productive, but social and political coordination to support the technological progress that solves our other externality problems is important.

More Examples

The pattern of the above examples is clear but there are still more I want to list, so I’ll go through the following ones faster.

Over-exploitation of Whales ==> Kerosene and petroleum lubricant

Whales were intensively hunted for their fats, first for light and then for industrial lubricants. Whaling controls were tried and mostly failed but we invented other materials to use instead and now whale populations are rebounding.

Ivory Poaching ==> Plastics

A similar story to the whales. Ivory was the best available material for precisely shaped objects that still needed hardness like combs and billiard balls. Elephants were hunted close to extinction until plastics and other materials were invented that were better than ivory for this purpose.

Horse Manure ==> Automobiles

Horses caused massive negative externality problems. There were 130,000 horses working in Manhattan in 1900 that each produced 45 pounds of manure a day. Millions of pounds of manure and hundreds of horse carcasses created near-unbearable stink, carried disease, attracted pests, and leeched into the water supply.

Lots of regulations were passed attempting to control this but unpriced externalities remained and even the optimal tradeoff was still shitty. Cars have their own significant externalities but they solved these problems better than any coordination could have.

Wood Cooking Stoves ==> Electric and Gas

This is similar to the Pittsburgh story I opened with. Particulate pollution in the developing world is a massive health risk, with a big source coming from wood fired cook stoves. As these countries develop, they are replacing these with electric or gas stoves which are better both privately and socially.

The transition away from wood as a construction material and fuel also solves de-forestation externalities. De-forestation has also been stopped in the developed world by growth in farming land-use efficiency.

Waterborne Disease ==> Modern Plumbing and Water Treatment

Chemical purification of water, mass produced steel and concrete for sewage infrastructure, and inoculations against waterborne disease have been the major forces addressing this externality, though political and social coordination to build the infrastructure has also been important.

Carbon Emissions ==> Solar Power

Carbon emissions are perhaps the first example of an externality people would think of. We could have a carbon tax that would help abate this problem, but we don’t and it doesn’t seem likely anytime soon. But the rapid improvements in solar power will make the socially optimal energy technology into the cheapest one too.

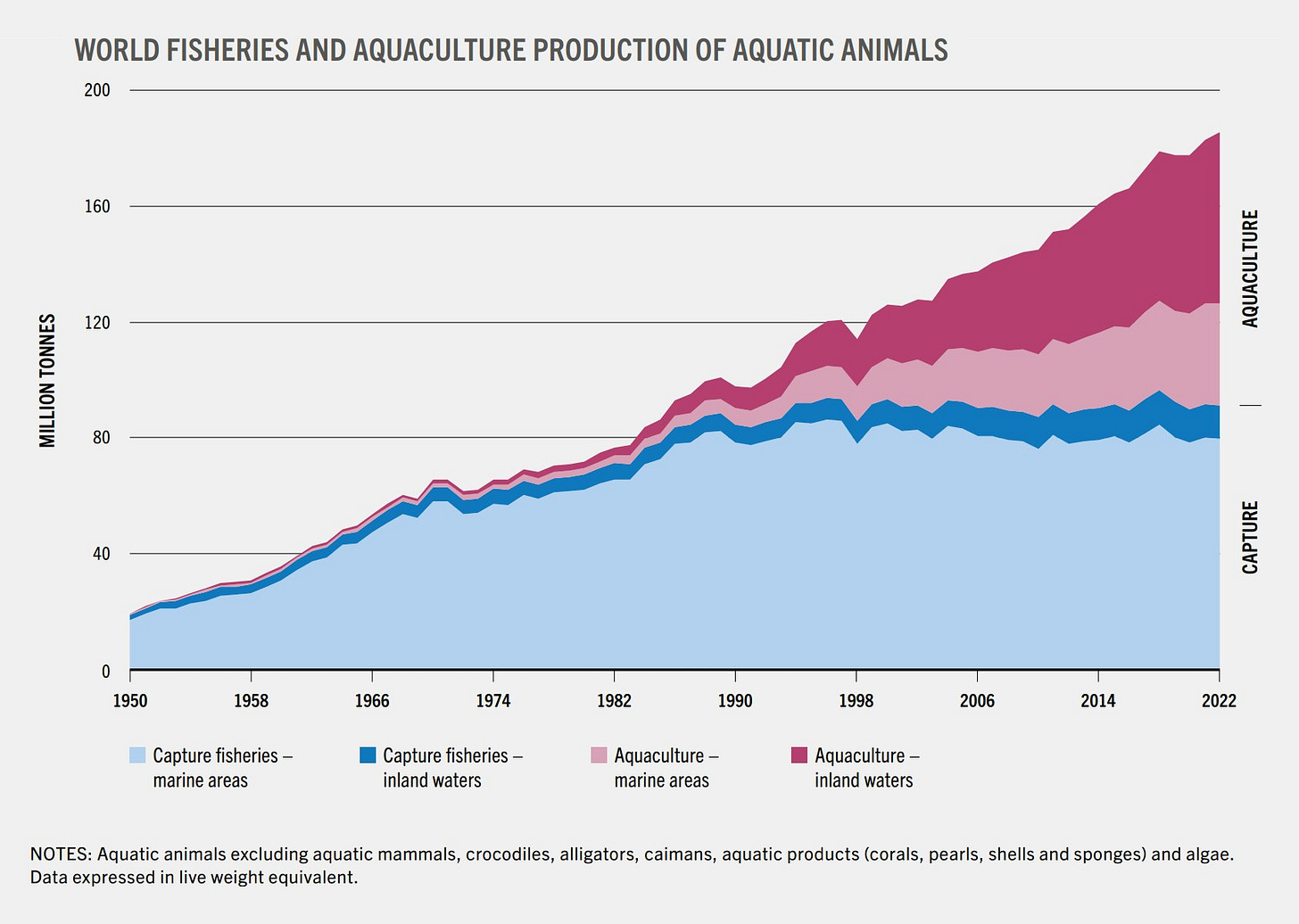

Overfishing ==> Aquaculture

Fishery property rights are still frequently contested which leads to tragedy of the commons problems. Aquaculture, or the farming of fish resources, addresses these externalities and is growing to be the major source of fish.

That's reasonable enough, but it was coordination that drove the technology. It was the restrictions on coal use that led people to shift to alternate energy sources. It was that coordinated push that made bringing in natural gas and the infrastructure for it to make economic sense. If it was just about technology without coordination, we'd have seen better air filtration systems for homes and workplaces slowly accelerate, not fuel replacement and emissions control technology.

There's something naive about the way many economists address problems that involve collective action. Collective action requires political and legal mechanisms, and economists don't like that, so they insist that economic forces alone are sufficient.

A good example was the bicyclist problem. People liked bicycles and the mobility they provided, but the roads were awful, cobblestones and mud. There was no way making economic decisions about bicycle technology were going to improve the roads. The roads were improved by collective action imposing a political solution. The better roads made bicycles better and also - sigh - paved the way for automobiles.

You had this problem with electrical power. It was limited by the need to use batteries or having a local generator. It didn't make economic sense for a single factory to replace a steam powered prime mover with a generator, however, coordinated action to encourage and convince the public of the safety of electric power along public conduits made regional generation facilities practical.

Technology may provide a long term solution. (e.g. There was no way to implement congestion pricing without creating worse problems without recent technology.) However, coordinated action is frequently necessary to drive the technology.

What about congestion? Seems to me congestion pricing is only solution here and technology actually enables us to do a good job.